- Poems Poetry Art

- Author

- Alfred French (11)

- Charles Bukowski (12)

- Clarence F Underwood (6)

- Edgar Allan Poe (16)

- Edmund Spenser (7)

- Eyvind Earle (15)

- Jack Hirschman (16)

- John Hejduk (9)

- John Milton (7)

- Lance Woolaver (7)

- Lindley Murray (8)

- Patti Smith (16)

- Reilly Rhodes (11)

- Rosaleen Norton (6)

- Shel Silverstein (9)

- Unknown (9)

- Various (40)

- William Blake (9)

- William Shakespeare (7)

- Wulf Segebrecht (17)

- ... (3209)

- Binding

- Language

- Arabic (3)

- Czech & English (11)

- Dutch (5)

- Eng, Gec (3)

- English (1340)

- English, Japanese (3)

- English, Persian (3)

- English, Russian (9)

- French (43)

- Germ, German (4)

- German (45)

- German, Germ (12)

- Hebrew (3)

- Italian (11)

- Japanese (18)

- Latin (11)

- Persian (7)

- Portuguese (3)

- Russian (19)

- Spanish (13)

- ... (1881)

- Publisher

- Abrams, Inc. (12)

- Bernard Lintott (6)

- Brill (6)

- Broadside Press (10)

- De Selliers, Diane (10)

- E. Little & Co (8)

- George Olms (16)

- Gotham Press (9)

- Hard Press (15)

- Harpercollins (7)

- J.b. Metzlersche (17)

- Museum Of Modern Art (9)

- Nimbus Publishing (7)

- Rizzoli (9)

- Samuel French (7)

- Sore Dover Press (7)

- Ten Crow Press (6)

- Thames & Hudson (6)

- Unknown (11)

- X-ray Book Company (6)

- ... (3263)

- Region

- Signed

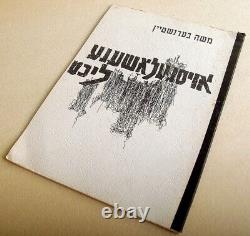

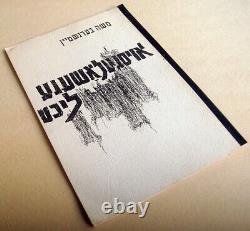

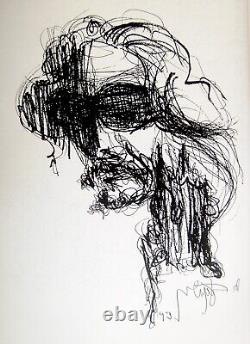

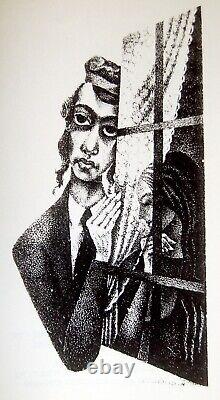

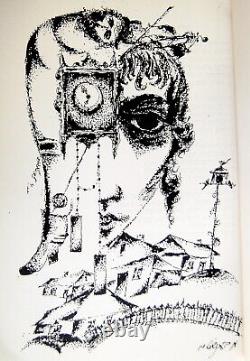

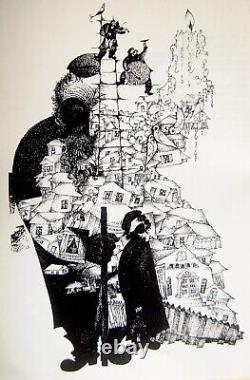

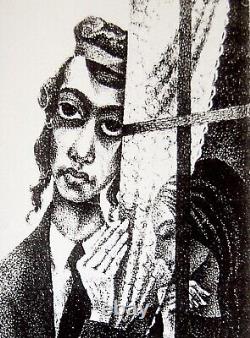

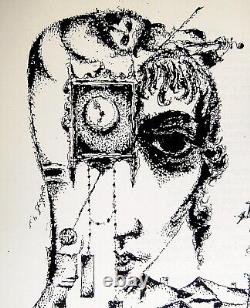

SIGNED Jewish YIDDISH Poetry ART BOOK Polish HOLOCAUST Judaica SHTETL Israel

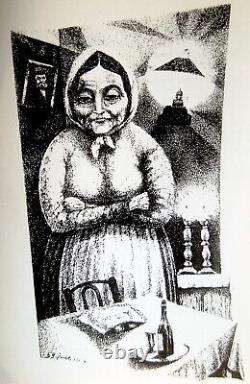

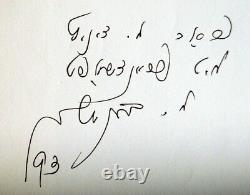

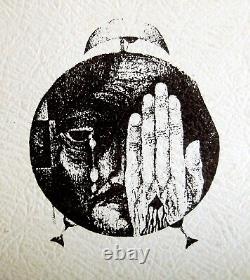

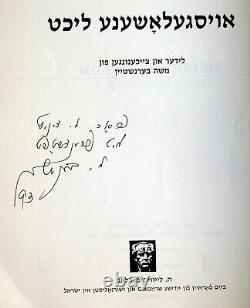

The HOLOCAUST SURVIVOR Tel Aviv POLISH-ISRAELI ARTIST Moshe BERNSTEIN has dedicated his whole JEWISH - POLISH ART to the DESTRUCTED Jewish-Yiddish SHTETL (Stetl) Sights, Types, Images, Famillies, Alleys and Streets. IMAGES which were perished forever after the total destruction in the HOLOPCAUST. This is a POEM ART BOOK which he wrote by himself in YIDDISH, Obviously accompanied by his own DRAWINGS and PAINTINGS. The Yiddish POEM ART BOOK was published in Tel Aviv in 1993 in a very limited personal edition. The book was SIGNED and INSCRIBED by the ARTIST in YIDDISH.

Size around 8.5 x 11.5.21 one sided leaves. (Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images) Book will be sent inside a protective packaging. Will be sent inside a protective rigid packaging. He graduated from Vilna Academy of Art in 1939. His family was wiped out in the Holocaust, but he survived the war and remained in Russia until 1947, when he attempted to immigrate illegally to the Land of Israel with Aliyah Bet.

He ended up in a detention camp in Cyprus, where he remained until the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. He fought in the War of Independence.

Bernstein's art focused on his memories from the shtetl. In 1999, the Massuah Institute for the Study of the Holocaust awarded him a prize for his documentation of a vanished world. He also illustrated volumes of Yiddish poetry and other books.

Born in Poland in 1920, Bernstein completed his art studies in the Academy of Vilna in 1939. His family was wiped out in the Holocaust, but he survived the war and lived in Russia until 1947, when he immigrated to Palestine as part of the "illegal immigration" (aliyah bet). He was caught and spent time in a detention camp in Cyprus. Bernstein's artistic path in Israel recalls that of other painters who reflected their memories of small Jewish Diaspora towns, or shtetls. At a certain stage, these artists were rejected by the local art scene.In the 1950s,'60s and'70s, the subject aroused public interest and recognition. In 1948, Bernstein participated in a group exhibit in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, and in 1949 in a group exhibit at Artists' House (then known as the Artists' Pavilion). In 1954, he participated in another exhibition - of young artists - in the Tel Aviv Museum. In 1962, he had a solo exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum, another in 1967 at the Haifa Museum, and a retrospective in 1973 in the Ein Harod Museum of Art. Interspersed among these events were shows at the Katz and Chemerinsky Galleries in Tel Aviv.

A Bernstein exhibit, which included paintings of the shtetl, was shown in 1998 at the international theater festival in Parma, Italy. In 1999, he was awarded a prize by the Massuah Institute for the Study of the Holocaust, for his documentation of the world that vanished at the beginning of his career.

" His paintings appeared on the walls of the defunct Kassit cafe in Tel Aviv, and in the Kiton restaurant - "places in which he ate and gave paintings, says gallery owner Zaki Rosenfeld, whose father, Eliezer Rosenfeld, worked with Bernstein. Bernstein's paintings always touched on memories of the Jewish town he was forced to leave at a young age. They were a constant reminder of the destruction of European Jewry, but also expressed great yearning.

Bernstein wrote in the catalogue of the 1973 exhibition in Ein Harod: In this exhibition, I once again bring you the experiences and dreams of my longed-for past, because for me it is an enchanted garden which I walk as if intoxicated by its fragrances and its beauty, and from which I draw the inspiration for my work. " "Moshe was one of those young artists who gave expression to a different kind of experience in that period, says Galia Bar-Or, curator and director of the Ein Harod Museum of Art. He is perceived as the kind of Jewish artist that gives sentimental expression to the memory of a Jewish culture that is gone forever. He also illustrated books of Yiddish poetry.He did the typography by hand, in black ink; and in his decorations around the sides there appeared that same figure of a Jewish girl, with a black braid and big eyes, and the houses of the town. Among others, he illustrated Israel Ch.

Biletzky's book, "A Jewish Shtetl, " which was published in 1986. "My father, who also came from the shtetl, worked with him for years, and loved his work, " says Zaki Rosenfeld about Bernstein.He belonged to that same vanishing group of artists who represented and preserved the cultural fabric from which they themselves came. When I turned the gallery into a gallery of contemporary art, he would walk down Dizengoff Street, look at the gallery, spit on the ground, make sure I had seen him, and continue on his way. There is no doubt that the face of this little man, and what he represented, will be missed on the Tel Aviv landscape.

, diminutive form of Yiddish shtot????? , "town", pronounced very similarly to the South German diminutive "Städtle", "little town; cf. MHG: stetelîn, stetlîn, stetel was typically a small town with a large Jewish population in pre-Holocaust Central and Eastern Europe. , shtetlekh) were mainly found in the areas which constituted the 19th century Pale of Settlement in the Russian Empire, the Congress Kingdom of Poland, Galicia, and Romania. A larger city, like Lemberg or Czernowitz, was called a shtot (Yiddish:?????); a smaller village was called a dorf (Yiddish:????? The concept of shtetl culture is used as a metaphor for the traditional way of life of 19th-century Eastern European Jews.

Shtetls are portrayed as pious communities following Orthodox Judaism, socially stable and unchanging despite outside influence or attacks. The Holocaust resulted in the disappearance of the vast majority of shtetls, through both extermination and mass exodus to the United States and what would become Israel. Origins The history of the oldest Eastern European shtetls began about a millennium ago and saw periods of relative tolerance and prosperity as well as times of extreme poverty, hardships and pogroms.The attitudes and thought habits characteristic of the learning tradition are as evident in the street and market place as the yeshiva. The popular picture of the Jew in Eastern Europe, held by Jew and Gentile alike, is true to the Talmudic tradition. The picture includes the tendency to examine, analyze and re-analyze, to seek meanings behind meanings and for implications and secondary consequences.

It includes also a dependence on deductive logic as a basis for practical conclusions and actions. In life, as in the Torah, it is assumed that everything has deeper and secondary meanings, which must be probed. All subjects have implications and ramifications. Moreover, the person who makes a statement must have a reason, and this too must be probed. Often a comment will evoke an answer to the assumed reason behind it or to the meaning believed to lie beneath it, or to the remote consequences to which it leads. The process that produces such a response-- often with lightning speed-- is a modest reproduction of the pilpul process. [1] Not only did the Jews of the shtetl speak a unique language (Yiddish), but they also had a unique rhetorical style, rooted in traditions of Talmudic learning: In keeping with his own conception of contradictory reality, the man of the shtetl is noted both for volubility and for laconic, allusive speech. Both pictures are true, and both are characteristic of the yeshiva as well as the market places. When the scholar converses with his intellectual peers, incomplete sentences a hint, a gesture, may replace a whole paragraph. The listener is expected to understand the full meaning on the basis of a word or even a sound... Such a conversation, prolonged and animated, may be as incomprehensible to the uninitiated as if the excited discussants were talking in tongues. The same verbal economy may be found in domestic or business circles. [1] The shtetl operates on a communal spirit where giving to the needy is not only admired, but expected and essential: The problems of those who need help are accepted as a responsibility both of the community and of the individual. They will be met either by the community acting as a group, or by the community acting through an individual who identifies the collective responsibility as his own...The rewards for benefaction are manifold and are to be reaped both in this life and in the life to come. On earth, the prestige value of good deeds is second only to that of learning. [1] This approach to good deeds finds its roots in Jewish religious views, summarized in Pirkei Avot by Shimon Hatzaddik's "three pillars":On three things the world stands. On Torah, On service [of God], And on acts of human kindness. [2] Tzedaka (charity) is a key element of Jewish culture, both secular and religious, to this day.

It exists not only as a material tradition e. G tzedaka boxes, but also immaterially, as an ethos of compassion and activism for those in need. Material things were neither disdained nor extremely praised in the shtetl. Menial labor was generally looked down upon as prost, or prole. Even the poorer classes in the shtetl tended to work in jobs that required the use of skills, such as shoe-making or tailoring of clothes.

The shtetl had a consistent work ethic which valued hard work and frowned upon laziness. Studying, of course, was considered the most valuable and hard work of all. Interaction with Gentiles The shtetl's main interaction with Gentile citizens was in trading with the neighboring peasants.

There was often animosity towards the Jews from these peasants, resulting in extremely violent pogroms from the Gentiles on the Jews, resulting in many Jewish deathswhen? This, among other things, helped foster a very strong "us-them" mentality based on differences between the peoples[vague]. This can be seen in the play Fiddler on the Roofunreliable source? Collapse The May Laws introduced by Tsar Alexander III of Russia in 1882 banned Jews from rural areas and towns of fewer than ten thousand people.In the 20th century revolutions, civil wars, industrialization and the Holocaust destroyed traditional shtetl existence. However, Hasidic Jews have founded new communities in the United States, such as Kiryas Joel and New Square.

There is a belief found in historical and literary writings that the shtetl disintegrated before it was destroyed during World War II; however, this alleged cultural break-up is never clearly defined. [3] The shtetl in fiction and folklore Chelm figures prominently in the Jewish humor as the legendary town of fools. Kasrilevke, the setting of many of Sholom Aleichem's stories, and Anatevka, the setting of the musical Fiddler on the Roof (based on other stories of Sholom Aleichem) are other notable fictional shtetls.The 2002 novel Everything Is Illuminated, by Jonathan Safran Foer, tells a fictional story set in the Ukrainian shtetl Trachimbrod. (Trochenbrod) The 1992 children's book Something from Nothing, written and illustrated by Phoebe Gilman, is an adaptation of a traditional Jewish folktale set in a fictional shtetl. In 1996 the Frontline programme Shtetl broadcast; it was about Polish Christian and Jewish relations. Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich, better known under his pen name Sholem Aleichem (Yiddish and Hebrew:????????????

during the Soviet era[citation needed]; Russian and Ukrainian:?????? February 18 1859 - May 13, 1916, was a leading Yiddish author and playwright.

The musicalFiddler on the Roof, based on his stories about Tevye the Dairyman, was the first commercially successful English-language stage production about Jewish life in Eastern Europe. The Hebrew phrase Shalom aleichem literally means "Peace be upon you", and is a greeting in traditional Hebrew and Yiddish. Contents [hide] 1 Biography 2 Literary career 3 Critical reception 4 Beliefs and activism 5 Death 6 Commemoration and legacy 7 Published works 7.1 English-language collections 7.2 Autobiography 7.3 Novels 7.3.1 Young adult literature 7.4 Plays 7.5 Miscellany 8 References 9 Further reading 10 External links Biography[edit] Solomon Naumovich (Sholom Nohumovich) Rabinovich Russian:????????????????? was born in 1859 in Pereyaslav and grew up in the nearby shtetl (small town with a large Jewish population) of Voronko, in the Poltava Governorate of the Russian Empire (now in the Kiev Oblast of centralUkraine). [1] His father, Menachem-Nukhem Rabinovich, was a rich merchant at that time.

[2] However, a failed business affair plunged the family into poverty and Solomon Rabinovich grew up in reduced circumstances. [2] When he was 13 years old, the family moved back to Pereyaslav, where his mother, Chaye-Esther, died in a cholera epidemic.[3] Sholem Aleichem's first venture into writing was an alphabetic glossary of the epithets used by his stepmother. At the age of fifteen, inspired by Robinson Crusoe, he composed a Jewish version of the novel. He adopted the pseudonymSholem Aleichem, a Yiddish variant of the Hebrew expression shalom aleichem, meaning "peace be with you" and typically used as a greeting. In 1876, after graduating from school in Pereyaslav, he spent three years tutoring a wealthy landowner's daughter, Olga (Hodel) Loev (1865 - 1942).

[4] From 1880 to 1883 he served as crown rabbi inLubny. [5] On May 12, 1883, he and Olga married, against the wishes of her father. A few years later, they inherited the estate of Olga's father. In 1890, Sholem Aleichem lost their entire fortune in a stock speculation and fled from his creditors. Solomon and Olga had their first child, a daughter named Ernestina (Tissa), in 1884.

[6] Daughter Lyalya (Lili) was born in 1887. As Lyalya Kaufman, she became a Hebrew writer. Lyalya's daughter Bel Kaufman, also a writer, was the author of Up the Down Staircase, which was also made into a successful film. A third daughter, Emma, was born in 1888.

In 1889, Olga finally gave birth to a son. They named him Elimelech, after Olga's father, but at home they called him Misha. Daughter Marusi (who would one day publish "My Father, Sholom Aleichem" under her married name Marie Waife-Goldberg) was born in 1892. A final child, a son named Nochum (Numa) after Solomon's father was born in 1901 (under the name Norman Raeben he became a painter and an influential art teacher).After witnessing the pogroms that swept through southern Russia in 1905, Sholem Aleichem left Kiev and resettled to New York City, where he arrived in 1906. His family[clarification needed] set up house in Geneva, Switzerland, but when he saw he could not afford to maintain two households, he joined them in Geneva in 1908. Despite his great popularity, he was forced to take up an exhausting schedule of lecturing to make ends meet.

In July 1908, during a reading tour in Russia, Sholem Aleichem collapsed on a train going through Baranowicze. He was diagnosed with a relapse of acute hemorrhagic tuberculosis and spent two months convalescing in the town's hospital.

He later described the incident as "meeting his majesty, the Angel of Death, face to face", and claimed it as the catalyst for writing his autobiography, Funem yarid [From the Fair]. [1] He thus missed the first Conference for the Yiddish Language, held in 1908 in Czernovitz; his colleague and fellow Yiddish activist Nathan Birnbaum went in his place. [7] Sholem Aleichem spent the next four years living as a semi-invalid.

During this period the family was largely supported by donations from friends and admirers. Sholem Aleichem moved to New York City again with his family in 1914. The family lived in the Lower East Side, Manhattan. His son, Misha, ill with tuberculosis, was not permitted entry under United States immigration laws and remained in Switzerland with his sister Emma.

Sholem Aleichem died in New York in 1916. Literary career[edit] A volume of Sholem Aleichem stories in Yiddish, with the author's portrait and signature Like his contemporaries Mendele Mocher Sforim and I. Peretz, Sholem Rabinovitch started writing in Hebrew, as well as inRussian. In 1883, when he was 24 years old, he published his first Yiddish story, Tsvey Shteyner ("Two Stones"), using for the first time the pseudonym Sholem Aleichem. By 1890 he was a central figure in Yiddish literature, the vernacular language of nearly all East European Jews, and produced over forty volumes in Yiddish.

It was often derogatorily called "jargon", but Sholem Aleichem used this term in an entirely non-pejorative sense. Apart from his own literary output, Sholem Aleichem used his personal fortune to encourage other Yiddish writers. In 1888-89, he put out two issues of an almanac, Di Yidishe Folksbibliotek ("The Yiddish Popular Library") which gave important exposure to young Yiddish writers. In 1890, after he lost his entire fortune, he could not afford to print the almanac's third issue, which had been edited but was subsequently never printed.Tevye the Dairyman was first published in 1894. Over the next few years, while continuing to write in Yiddish, he also wrote in Russian for an Odessa newspaper and for Voskhod, the leading Russian Jewish publication of the time, as well as in Hebrew for Ha-melitz, and for an anthology edited by YH Ravnitzky. It was during this period that Sholem Aleichem contracted tuberculosis. In August 1904, Sholem Aleichem edited Hilf: a Zaml-Bukh fir Literatur un Kunst ("Help: An Anthology for Literature and Art"; Warsaw, 1904) and himself translated three stories submitted by Tolstoy (Esarhaddon, King of Assyria; Work, Death and Sickness; Three Questions) as well as contributions by other prominent Russian writers, including Chekhov, in aid of the victims of the Kishinev pogrom.

Critical reception[edit] Sholem Aleichem's narratives were notable for the naturalness of his characters' speech and the accuracy of his descriptions of shtetl life. Early critics focused on the cheerfulness of the characters, interpreted as a way of coping with adversity.

Later critics saw a tragic side in his writing. [8] He was often referred to as the "Jewish Mark Twain" because of the two authors' similar writing styles and use of pen names. Both authors wrote for both adults and children, and lectured extensively in Europe and the United States. [9] Beliefs and activism[edit] Sholem Aleichem was an impassioned advocate of Yiddish as a national Jewish language, which he felt should be accorded the same status and respect as other modern European languages. He did not stop with what came to be called "Yiddishism", but devoted himself to the cause of Zionism as well. Many of his writings[10] present the Zionist case.In 1888, he became a member of Hovevei Zion. In 1907, he served as an American delegate to the Eighth Zionist Congress held in The Hague. Sholem Aleichem had a mortal fear of the number 13. His manuscripts never had a page 13; he numbered the thirteenth pages of his manuscripts as 12a.

[11]Though it has been written that even his headstone carries the date of his death as "May 12a, 1916", [12] his headstone reads the dates of his birth and death in Hebrew, the 26th of Adar and the 10th of Iyar, respectively. Death[edit] Sholem Aleichem's funeral on May 15, 1916 Sholem Aleichem died in New York on May 13, 1916 from tuberculosis and diabetes, [13] aged 57, while working on his last novel, Motl, Peysi the Cantor's Son, and was buried at Old Mount Carmel cemetery in Queens. [14] At the time, his funeral was one of the largest in New York City history, with an estimated 100,000 mourners. [15][16] The next day, his will was printed in the New York Times and was read into the Congressional Record of the United States.

Commemoration and legacy[edit] A 1959 Soviet Unionpostage stampcommemorating the centennial of Sholem Aleichem's birth Sholem Aleichem's will contained detailed instructions to family and friends with regard to burial arrangements and marking his yahrtzeit. He told his friends and family to gather, read my will, and also select one of my stories, one of the very merry ones, and recite it in whatever language is most intelligible to you.

" "Let my name be recalled with laughter, " he added, "or not at all. The celebrations continue to the present-day, and, in recent years, have been held at the Brotherhood Synagogue on Gramercy Park South in New York City, where they are open to the public. [17] In 1997, a monument dedicated to Sholem Aleichem was erected in Kiev; another was erected in 2001 in Moscow.

The main street of Birobidzhan is named after Sholem Aleichem;[18] streets were named after him also in other cities in the Soviet Union, among them Kiev, Odessa, Vinnytsia, Lviv, Zhytomyr and Mykolaiv (although this last one is now named after Karl Liebknecht[19]). In New York City in 1996, East 33rd Street between Park and Madison Avenue was renamed "Sholem Aleichem Place". Many streets in Israel are named after him. An impact crater on the planet Mercury also bears his name. [20] On March 2, 2009 (150 years after his birth) the National Bank of Ukraine issued an anniversary coin celebrating Aleichem with his face depicted on it. [21] Vilnius, Lithuania has a Jewish school named after him, in Melbourne, Australia a Yiddish school is named in his name. [22] Several Jewish schools in Argentinawere also named after him. [citation needed] In Rio de Janeiro, Brazil a library named BIBSA - Biblioteca Sholem Aleichem was founded in 1915 as a Zionist institution but some years later Jews of left-wing assumed the power by regular internal polls, and Sholem Aleichem started to mean Communism in Rio de Janeiro.BIBSA had a very active theatrical program in Yiddish for more than 50 years since its foundation and of course Sholem Aleichem scripts were a must. In 1947 BIBSA evolved in a more complete club named ASA - Associação Sholem Aleichem that exists nowadays in Botafogo neighborhood.

Next year, in 1916 same group that created BIBSA, founded a Jewish school named Escola Sholem Aleichem that was closed in 1997. It was Zionist too, and became Communist like BIBSA, but after the 20th Communist Congress in 1956 school supporters and teachers split as a lot of Jews abandoned Communism and founded another school, Colégio Eliezer Steinbarg, still existing as one of the best Jewish schools in Brazil, named after the first director of Sholem Aleichem School, he himself, a Jewish writer born in Romania, that came to Brazil. [23][24] In the Bronx, New York, a housing complex called The Shalom Aleichem Houses[25] was built by Yiddish speaking immigrants in the 1920s, and was recently restored by new owners to its original grandeur. The Shalom Alecheim Houses are part of a proposed historic district in the area.

On May 13, 2016 an official Sholem Aleichem website [26] was launched to mark the 100th anniversary of Sholem Aleichem's death. [27] The website is a partnership between Sholem Aleichem's family, [28] his biographer Professor Jeremy Dauber, [29] Citizen Film, Columbia University's Center for Israel and Jewish Studies, [30] The Covenant Foundation, [31] and The Yiddish Book Center. The website features interactive maps and timelines, [32] recommended readings, [33] as well as a list of centennial celebration events taking place worldwide. [34] The website also features resources for educators. The stories which form the basis for Fiddler on the Roof.The Best of Sholom Aleichem, edited by R. Howe (originally published 1979), Walker and Co.

Tevye the Dairyman and the Railroad Stories, translated by H. A Treasury of Sholom Aleichem Children's Stories, translated by Aliza Shevrin, Jason Aronson, 1996, ISBN 1-56821-926-1. Inside Kasrilovka, Three Stories, translated by I. Goldstick, Schocken Books, 1948 (variously reprinted) The Old Country, translated by Julius & Frances Butwin, J B H of Peconic, 1999, ISBN 1-929068-21-2. Stories and Satires, translated by Curt Leviant, Sholom Aleichem Family Publications, 1999, ISBN 1-929068-20-4.

Selected Works of Sholem-Aleykhem, edited by Marvin Zuckerman & Marion Herbst (Volume II of "The Three Great Classic Writers of Modern Yiddish Literature"), Joseph Simon Pangloss Press, 1994, ISBN 0-934710-24-4. Some Laughter, Some Tears, translated by Curt Leviant, Paperback Library, 1969, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 68-25445. Novels[edit] Stempenyu, originally published in his Folksbibliotek, adapted 1905 for the play Jewish Daughters. Yossele Solovey (1889, published in his Folksbibliotek) Tevye's Daughters, translated by F. Mottel the Cantor's son.

English version: Henry Schuman, Inc. New York 1953 In The Storm Wandering Stars Marienbad, translated by Aliza Shevrin 1982, G. Putnam Sons, New York from original Yiddish manuscript copyrighted by Olga Rabinowitz in 1917 The Bloody Hoax Menahem-Mendl, translated as The Adventures of Menahem-Mendl, translated by Tamara Kahana, Sholom Aleichem Family Publications, 1969, ISBN 1-929068-02-6. Young adult literature[edit] Motl peysi dem khazns, translated as The Adventures of Mottel, the Cantor's Son (young adult literature), translated by Tamara Kahana, Sholom Aleichem Family Publications, 1999, ISBN 1-929068-00-X.

Also appeared as Mottel the Cantor's son Henry Schuman, Inc. New York 1953 The Bewitched Tailor, Sholom Aleichem Family Publications, 1999, ISBN 1-929068-19-0. Plays[edit] The Doctor (1887), one-act comedy Der get (The Divorce, 1888), one-act comedy Di asife (The Assembly, 1889), one-act comedy Yaknez (1894), a satire on brokers and speculators Tsezeyt un tseshpreyt (Scattered Far and Wide, 1903), comedy Agentn (Agents, 1908), one-act comedy Yidishe tekhter (Jewish Daughters, 1905) drama, adaptation of his early novel Stempenyu Di goldgreber (The Golddiggers, 1907), comedy Shver tsu zayn a yid (Hard to Be a Jew / If I Were You, 1914) Dos groyse gevins (The Big Lottery / The Jackpot, 1916) Tevye der milkhiker, (Tevye the Milkman, 1917, performed posthumously) ebay370 folder 176.