- Poems Poetry Art

- Edition

- Features

- 1st Edition (34)

- Antique (4)

- Canvas (5)

- Dust Jacket (23)

- Embossed (4)

- Framed (124)

- Framed Poster (9)

- Framed, Matted (4)

- Hardcover (5)

- Illustrated (63)

- Limited Edition (29)

- Matted (17)

- New Edition (4)

- Numbered (17)

- One Of A Kind (ooak) (24)

- Personalized (4)

- Signed (176)

- Unframed (4)

- Vintage (8)

- Vintage Paperback (6)

- ... (2887)

- Format

- Board Book (2)

- Books (3)

- Box Set (2)

- Broadside (2)

- Chapbook / Pamphlet (9)

- Cover Rigid (3)

- Hard Cover (2)

- Hardback (10)

- Hardcover (501)

- Leather (6)

- Library Binding (2)

- Mixed Lot (6)

- Paperback (101)

- Paperback / Softback (4)

- Perfect (8)

- Physical (6)

- Record (2)

- Softcover (13)

- Trade Paperback (122)

- Unknown (8)

- ... (2639)

- Language

- Arabic (3)

- Czech & English (11)

- Dutch (5)

- Eng, Gec (3)

- English (1340)

- English, Japanese (3)

- English, Persian (3)

- English, Russian (9)

- French (43)

- Germ, German (4)

- German (45)

- German, Germ (13)

- Hebrew (3)

- Italian (11)

- Japanese (18)

- Latin (11)

- Persian (7)

- Portuguese (3)

- Russian (19)

- Spanish (13)

- ... (1884)

- Publisher

- Abrams, Inc. (12)

- Bernard Lintott (6)

- Broadside Press (10)

- De Selliers, Diane (10)

- E. Little & Co (8)

- George Olms (17)

- Gotham Press (9)

- Hard Press (15)

- Harpercollins (7)

- J.b. Metzlersche (17)

- Museum Of Modern Art (9)

- Nimbus Publishing (7)

- Pré Nian Editions (6)

- Rizzoli (9)

- Samuel French (7)

- Sore Dover Press (7)

- Ten Crow Press (6)

- Thames & Hudson (6)

- Unknown (11)

- X-ray Book Company (6)

- ... (3266)

- Type

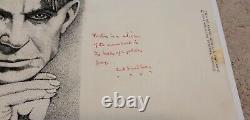

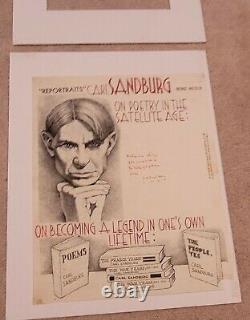

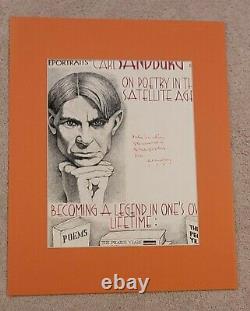

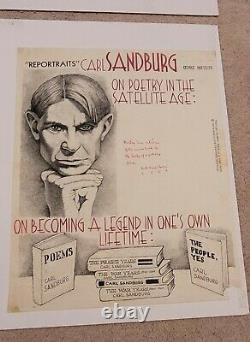

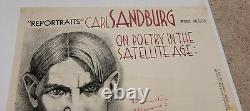

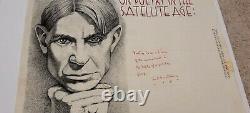

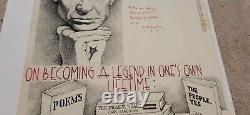

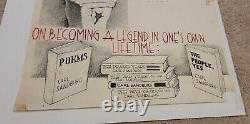

Awesome Carl Sandburg Handwritten Poem And Artwork Very Rare Detroit Cartoonist

CARL SANDBURG AUTOGRAPH QUOTATION SIGNED ON ORIGINAL "REPORTRAIT" PAGE BY DETRPIT ARTIST GEORGE HAESSLER. 16.5 X 14 " ; SOME STAINING, ONE BOTTOM CORNER MISSING ELSE A NICE PIECE WITH ORIGINASL INK PORTRAIT CARL SANDBURG, IMAGES OF SOME OF HIS BOOKS AT BOTTOM OF PAGE, WITH SPACE LEFT BLANK FOR SANDBURG'S COMMENTS ON THIS TOPIC: "ON POETRY IN THE SATTELITE AGE. SANDBURG WRITES: "POETRY IS A SILVER OF THE MOON LIST IN THE BELLY OF A GOLDEN FROG".

SANDBURG SIGNED HIS NAME AND WRITES 1959. HAESSLER, A LOCAL ARTIST AND CARTOONIST, DID A SERIES OF THESE "REPORTRAITS" OF FAMOUS PEOPLE FOR THIS PUBLICATION. Carl Sandburg was born in Galesburg, Illinois, on January 6, 1878.His parents, August and Clara Johnson, had emigrated to America from the north of Sweden. After encountering several August Johnsons in his job for the railroad, the Sandburg's father renamed the family. The Sandburgs were very poor; Carl left school at the age of thirteen to work odd jobs, from laying bricks to dishwashing, to help support his family. At seventeen, he traveled west to Kansas as a hobo.

While serving, Sandburg met a student at Lombard College, the small school located in Sandburg's hometown. The young man convinced Sandburg to enroll in Lombard after his return from the war.

Sandburg worked his way through school, where he attracted the attention of Professor Philip Green Wright, who not only encouraged Sandburg's writing, but paid for the publication of his first volume of poetry, a pamphlet called Reckless Ecstasy (1904). While Sandburg attended Lombard for four years, he never received a diploma (he would later receive honorary degrees from Lombard, Knox College, and Northwestern University).After college, Sandburg moved to Milwaukee, where he worked as an advertising writer and a newspaper reporter. While there, he met and married Lillian Steichen (whom he called Paula), sister of the photographer Edward Steichen.

A Socialist sympathizer at that point in his life, Sandburg then worked for the Social-Democrat Party in Wisconsin and later acted as secretary to the first Socialist mayor of Milwaukee from 1910 to 1912. The Sandburgs soon moved to Chicago, where Carl became an editorial writer for the Chicago Daily News. Harriet Monroe had just started Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, and began publishing Sandburg's poems, encouraging him to continue writing in the free-verse, Whitman-like style he had cultivated in college.

Monroe liked the poems' homely speech, which distinguished Sandburg from his predecessors. It was during this period that Sandburg was recognized as a member of the Chicago literary renaissance, which included Ben Hecht, Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, and Edgar Lee Masters. He established his reputation with Chicago Poems (1916), and then Cornhuskers (1918), for which he received the Pulitzer Prize in 1919. Soon after the publication of these volumes Sandburg wrote Smoke and Steel (1920), his first prolonged attempt to find beauty in modern industrialism. With these three volumes, Sandburg became known for his free verse poems that portrayed industrial America. In the twenties, he started some of his most ambitious projects, including his study of Abraham Lincoln. From childhood, Sandburg loved and admired the legacy of President Lincoln.For thirty years he sought out and collected material, and gradually began the writing of the six-volume definitive biography of the former president. The twenties also saw Sandburg's collections of American folklore, the ballads in The American Songbag and The New American Songbag (1950), and books for children. These later volumes contained pieces collected from brief tours across America which Sandburg took each year, playing his banjo or guitar, singing folk-songs, and reciting poems. In the 1930s, Sandburg continued his celebration of America with Mary Lincoln, Wife and Widow (1932), The People, Yes (1936), and the second part of his Lincoln biography, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (1939), for which he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize. He received a second Pulitzer Prize for his Complete Poems in 1950.

Carl Sandburg died on July 22, 1967. Sandburg was inducted to the American Poets' Corner at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York in 2018. Slabs of the Sunburnt West (1922). Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years (1926). Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (1939). Mary Lincoln: Wife and Widow (1932). The New American Songbag (1950). Poet Carl Sandburg was born into a poor family in Galesburg, Illinois. He studied at Lombard College, and then moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where he worked as an organizer for the Socialist Democratic Party. In 1913, he moved to Chicago, Illinois and wrote for the Chicago Daily News. His first poems were published by Harriet Monroe in Poetry magazine. Sandburgs collection Chicago Poems (1916) was highly regarded, and he received the Pulitzer Prize for Corn Huskers (1918).His many subsequent books of poetry include The People, Yes (1936), Good Morning, America (1928), Slabs of the Sunburnt West (1922), and Smoke and Steel (1920). Trying to write briefly about Carl Sandburg, said a friend of the poet, is like trying to picture the Grand Canyon in one black and white snapshot. His range of interests was enumerated by his close friend, Harry Golden, who, in his study of the poet, called Sandburg the one American writer who distinguished himself in five fieldspoetry, history, biography, fiction, and music.

Sandburg composed his poetry primarily in free verse. Concerning rhyme versus non-rhyme Sandburg once said airily, If it jells into free verse, all right. If it jells into rhyme, all right. Some critics noted that the illusion of poetry in his works was based more on the arrangement of the lines than on the lines themselves. Sandburg, aware of the criticism, wrote in the preface to Complete Poems (1950), There is a formal poetry only in form, all dressed up and nowhere to go.

The number of syllables, the designated and required stresses of accent, the rhymes if wantedthey all come off with the skill of a solved crossword puzzle. A proficient and sometimes exquisite performer in rhymed verse goes out of his way to register the point that the more rhyme there is in poetry the more danger of its tricking the writer into something other than the urge in the beginning. He dismissed modern poetry, however, as a series of ear wigglings.

In Good Morning, America (1928), he published 38 definitions of poetry, among them: Poetry is a pack-sack of invisible keepsakes. Poetry is a sky dark with a wild-duck migration.

Poetry is the opening and closing of a door, leaving those who look through to guess about what is seen during a moment. His success as a poet was limited to that of a follower of Walt Whitman and of the Imagists.

In Carl Sandburg, Karl Detzer says that in 1918 admirers proclaimed him a latter-day Walt Whitman; objectors cried that their six-year-old daughters could write better poetry. Admirers of his poetry, however, have included Sherwood Anderson (among all the poets of America he is my poet), and Amy Lowell, who called Chicago Poems (1916) one of the most original books this age has produced. Lowells observations were reiterated by H. Mencken, who called Sandburg a true original, his own man.

No one, it is agreed, can deny the unique quality of his style. In his newspaper days, an old friend recalls, the slogan was, Print Sandburg as is. It was Sandburg, as Golden observes, who put America on paper, writing the American idiom, speaking to the masses, who held no terror for him. As Richard Crowder notes in Carl Sandburg, the poet Had been the first poet of modern times actually to use the language of the people as his almost total means of expression.

Sandburg had entered into the language of the people; he was not looking at it as a scientific phenomenon or a curiosity. He was at home with it. Did you know that all the work of the world is done through me?

He was always read by the masses, as well as by scholars. He once observed, Ill probably die propped up in bed trying to write a poem about America. Sandburgs account of the life of Abraham Lincoln is one of the monumental works of the century. Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (1939) alone exceeds in length the collected writings of Shakespeare by some 150,000 words.

Though Sandburg did deny the story that in preparation he read everything ever published on Lincoln, he did collect and classify Lincoln material for 30 years, moving himself into a garret, storing his extra material in a barn, and for nearly 15 years writing on a cracker-box typewriter. His intent was to separate Lincoln the man from Lincoln the myth, to avoid hero-worship, to relate with graphic detail and humanness the man both he and Whitman so admired.

Beard called the finished product a noble monument of American literature, written with indefatigable thoroughness. Allan Nevins saw it as homely but beautiful, learned but simple, exhaustively detailed but panoramic... [occupying] a niche all its own, unlike any other biography or history in the language. The Pulitzer Prize committee apparently agreed. Prohibited from awarding the biography prize for any work on Washington or Lincoln, it circumvented the rules by placing the book in the category of history.As a result of this work, Sandburg was the first private citizen to deliver an address before a joint session of Congress (on February 12, 1959, the 150th anniversary of Lincolns birth). Perhaps Sandburg was best known to America as the singing bardthe voice of America singing, says Golden. Sandburg was an author accepted as a personality, as was Mark Twain.

Requests for his lectures began to appear as early as 1908. He was his own accompanist, and was not merely a musician of sorts; he played the guitar well enough to have been a pupil of Andres Segovia. Sandburgs songs were projected by a voice in which you [could] hear farm hands wailing and levee Negroes moaning. It was fortunate that he was willing to travel about reciting and recording his poetry, for the interpretation his voice lent to his work was unforgettable. With its deep rich cadences, dramatic pauses, and Midwestern dialect, his speech was a kind of singing.Ben Hecht once wrote: Whether he chatted at lunch or recited from the podium he had always the same voice. He spoke like a man slowly revealing something. Sandburg was the recipient of numerous honorary degrees, had six high schools and five elementary schools named for him, and held news conferences with presidents at the White House. My father couldnt sign his name, wrote Sandburg; [he] made his mark on the CB&Q payroll sheet.

My mother was able to read the Scriptures in her native language, but she could not write, and I wrote of Abraham Lincoln whose own mother could not read or write! I guess that somewhere along in this youll find a story of America. A Sandburg archives is maintained in the Sandburg Room at the University of Illinois. Newman, who is known primarily as a Lincoln scholar but who also is the possessor of what is perhaps the largest and most important collection of Sandburgiana, has said that a complete bibliography of Sandburgs works, including contributions to periodicals and anthologies, forewords, introductions, and foreign editions would number more than 400 pages. Sandburg received 200 to 400 letters each week. For all this fame, he remained unassuming.What he wanted from life was to be out of jail... To get what I write printed... A little love at home and a little nice affection hither and yon over the American landscape...

[and] to sing every day. He wrote with a pencil, a fountain pen, or a typewriter, but I draw the line at dictating em, he said.

He kept his home as it was, refusing, for example, to rearrange his vast library in some orderly fashion; he knew where everything was. Furthermore, he said, I want Emerson in every room. On September 17, 1967, there was a National Memorial Service at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, at which Archibald MacLeish and Mark Van Doren read from Sandburgs poetry. A Carl Sandburg Exhibition of memorabilia was held at the Hallmark Gallery in New York City, from January to February, 1968, and his home is under consideration as a National Historical site. Sandburgs prose and poetry continues to inspire publication in new formats.The volume Arithmetic (1993), for example, presents Sandburgs famous poem of the same title in the form of a uniquely illustrated text for children. Sandburgs poem is a humorous commentary on the grade-school experience of learning arithmetic: Arithmetic is where numbers fly like pigeons in and out of your head. Reviewers praised the creative presentation of the poem, and the effectiveness of what School Library Journal reviewer JoAnn Rees called Ted Rands brightly colored, mixed-media anamorphic paintings. Also written for children, several of Sandburgs unpublished Rootabaga stories (also referred to as American fairy tales) have been posthumously collected by Sandburg scholar George Hendrick in More Rootabagas (1993).

Sandburg had published Rootabaga Pigeons in 1923 and Potato Face in 1930, leaving many other tales in the series unpublished. Critics praised the inventiveness, whimsicality, and humor of the stories, which feature such characters and places as The Potato Face Blind Man, Ax Me No Questions, and The Village of Liver and Onions. Sandburg was writing for the children in himself, comments Verlyn Klinkenborg in New York Times Book Review, for the eternal child, who, when he or she hears language spoken, hears rhythm, not sense. The papers belonged to Sandburgs editor until her death, when they were given to her nephew. Many items were obtained by the University of Illinois, where Sandburgs papers are held.

Author-poet Carl Sandburg was born in the three-room cottage at 313 East Third Street in Galesburg on January 6, 1878. The modest house, which is maintained by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, reflects the typical living conditions of a late nineteenth century working-class family. Many of the furnishings once belonged to the Sandburg family. Behind the home stands a small wooded park. There, beneath Remembrance Rock, lie the ashes of Carl Sandburg, who died in 1967.

Carl August Sandburg was born the son of Swedish immigrants August and Clara Anderson Sandburg. Carl, called "Charlie" by the family, was born the second of seven children in 1878.Carl Sandburg worked from the time he was a young boy. He quit school following his graduation from eighth grade in 1891 and spent a decade working a variety of jobs. He delivered milk, harvested ice, laid bricks, threshed wheat in Kansas, and shined shoes in Galesburg's Union Hotel before traveling as a hobo in 1897. His experiences working and traveling greatly influenced his writing and political views.

As a hobo he learned a number of folk songs, which he later performed at speaking engagements. He saw first-hand the sharp contrast between rich and poor, a dichotomy that instilled in him a distrust of capitalism. Upon his return to his hometown later that year, he entered Lombard College, supporting himself as a call fireman. Sandburg's college years shaped his literary talents and political views.

While at Lombard, Sandburg joined the Poor Writers' Club, an informal literary organization whose members met to read and criticize poetry. Poor Writers' founder, Lombard professor Phillip Green Wright, a talented scholar and political liberal, encouraged the talented young Sandburg. Sandburg honed his writing skills and adopted the socialist views of his mentor before leaving school in his senior year. Wright printed two more volumes for Sandburg, Incidentals (1907) and The Plaint of a Rose (1908). As the first decade of the century wore on, Sandburg grew increasingly concerned with the plight of the American worker. In 1907 he worked as an organizer for the Wisconsin Social Democratic party, writing and distributing political pamphlets and literature. At party headquarters in Milwaukee, Sandburg met Lilian Steichen, whom he married in 1908.The responsibilities of marriage and family prompted a career change. For several years he worked as a reporter for the Chicago Daily News, covering mostly labor issues and later writing his own feature. Sandburg was virtually unknown to the literary world when, in 1914, a group of his poems appeared in the nationally circulated Poetry magazine. Two years later his book Chicago Poems was published, and the thirty-eight-year-old author found himself on the brink of a career that would bring him international acclaim. Sandburg published another volume of poems, Cornhuskers, in 1918, and wrote a searching analysis of the 1919 Chicago race riots.

More poetry followed, along with Rootabaga Stories (1922), a book of fanciful children's tales. That book prompted Sandburg's publisher, Alfred Harcourt, to suggest a biography of Abraham Lincoln for children. Sandburg researched and wrote for three years, producing not a children's book, but a two-volume biography for adults. His Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years, published in 1926, was Sandburg's first financial success. He moved to a new home on the Michigan dunes and devoted the next several years to completing four additional volumes, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1940.Sandburg continued his prolific writing, publishing more poems, a novel, Remembrance Rock, a second volume of folk songs, and an autobiography, Always the Young Strangers. In 1945 the Sandburgs moved with their herd of prize-winning goats and thousands of books to Flat Rock, North Carolina. Sandburg's Complete Poems won him a second Pulitzer Prize in 1951.

Sandburg died at his North Carolina home July 22, 1967. In the small Carl Sandburg Park behind the house, his ashes were placed beneath Remembrance Rock, a red granite boulder. Ten years later the ashes of his wife were placed there. He was born in Galesburg, Illinois of Swedish parents and died in Flat Rock, North Carolina.Mencken called Carl Sandburg indubitably an American in every pulse-beat. He was a successful journalist, poet, historian, biographer, and autobiographer. During the course of his career, Sandburg won two Pulitzer Prizes, one for his biography of Abraham Lincoln The Complete Poems of Carl Sandburg. Much of his poetry, such as "Chicago", focused on Chicago, Illinois, where he spent time as a reporter for the Chicago Daily News and the Day Book. Following a brief (two-week) career as a student at West Point with Douglas MacArthur, Sandburg chose to attend Lombard College.

Sandburg left college without a degree in 1902 and married Lilian Steichen, sister of the famed photographer, Edward Steichen, in 1908. Lilian (nicknamed "Paus'l" by her mother and "Paula" by Carl) and Carl had three daughters. From 1912 to 1928, he lived in Chicago, nearby Evanston and Elmhurst. During this time he began work on his series of biographies on Abraham Lincoln, which would eventually earn him his Pulitzer Prize in history (for Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, 1940). Sandburg lived for a brief period in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, working as a secretary to Mayor Emil Seidel, the first socialist mayor in the United States, before moving to Harbert, Michigan. It was also during his years in the Chicago area and Milwaukee that Sandburg was a member of the Social Democratic Party and took a strong interest in the socialist community. In 1945, the Sandburg family moved from the Midwest, where they'd spent most of their lives, to the Connemara estate, in Flat Rock, North Carolina. Connemara was ideal for the family, as it gave Mr.Sandburg an entire mountain top to roam and enough solitude for him to write. Sandburg over 30 acres of pasture to raise and graze her prize-winning dairy goats. He is also beloved by generations of children for his Rootabaga Stories and Rootabaga Pigeons, a series of whimsical, sometimes melancholy stories he originally created for his own daughters. The Rootabaga Stories were born of Sandburg's desire for "American fairy tales" to match American childhood. He felt that the European stories involving royalty and knights were inappropriate, and so populated his stories with skyscrapers, trains, corn fairies and the "Five Marrrrvelous Pretzels".

His home of 22 years in Flat Rock, Henderson County, North Carolina is preserved by the National Park Service as the Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site. Carl Sandburg College is located in Sandburg's birthplace of Galesburg, Illinois. The Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign possesses the Carl Sandburg collection and archives. Carl August Sandburg (January 6, 1878 July 22, 1967) was an American poet, biographer, journalist, and editor. He won three Pulitzer Prizes: two for his poetry and one for his biography of Abraham Lincoln.

During his lifetime, Sandburg was widely regarded as "a major figure in contemporary literature", especially for volumes of his collected verse, including Chicago Poems (1916), Cornhuskers (1918), and Smoke and Steel (1920). [2] He enjoyed "unrivaled appeal as a poet in his day, perhaps because the breadth of his experiences connected him with so many strands of American life", [3] and at his death in 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson observed that Carl Sandburg was more than the voice of America, more than the poet of its strength and genius. Carl Sandburg was born in a three-room cottage at 313 East Third Street in Galesburg, Illinois to Clara Mathilda (née Anderson) and August Sandberg, [1] both of Swedish ancestry. [5] He adopted the nickname "Charles" or "Charlie" in elementary school at about the same time he and his two oldest siblings changed the spelling of their last name to "Sandburg". At the age of thirteen he left school and began driving a milk wagon. From the age of about fourteen until he was seventeen or eighteen, he worked as a porter at the Union Hotel barbershop in Galesburg. [8] After that he was on the milk route again for 18 months.He then became a bricklayer and a farm laborer on the wheat plains of Kansas. [9] After an interval spent at Lombard College in Galesburg, [10] he became a hotel servant in Denver, then a coal-heaver in Omaha.

He began his writing career as a journalist for the Chicago Daily News. Later he wrote poetry, history, biographies, novels, children's literature, and film reviews. Sandburg also collected and edited books of ballads and folklore. He spent most of his life in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan before moving to North Carolina. Sandburg was never actually called to battle.He attended West Point for just two weeks before failing a mathematics and grammar exam. He then moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin to work for a newspaper, and also joined the Wisconsin Social Democratic Party, the name by which the Socialist Party of America was known in the state. Sandburg served as a secretary to Emil Seidel, socialist mayor of Milwaukee from 1910 to 1912. Carl Sandburg later remarked that Milwaukee was where he got his bearings and that the rest of his life had been "the unrolling of a scene that started up in Wisconsin". Lilian's brother was the famous photographer Edward Steichen.

Sandburg with his wife, whom he called Paula, raised three daughters. Their first daughter, Margaret, was born in 1911. The Sandburgs moved to Harbert, Michigan, and then to suburban Chicago, Illinois in 1912 after he was offered a job by a Chicago newspaper.

[13] They lived in Evanston, Illinois before settling at 331 South York Street in Elmhurst, Illinois, from 1919 to 1930. During the time, Sandburg wrote Chicago Poems (1916), Cornhuskers (1918), and Smoke and Steel (1920). [2] In 1919 Sandburg won a Pulitzer Prize "made possible by a special grant from The Poetry Society" for his collection Cornhuskers. [14] Sandburg also wrote three children's books in Elmhurst: Rootabaga Stories, in 1922, followed by Rootabaga Pigeons (1923), and Potato Face (1930). Sandburg also wrote Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years, a two-volume biography, in 1926, The American Songbag (1927), and a book of poems called Good Morning, America (1928) in Elmhurst.

The Sandburg house at 331 South York Street in Elmhurst was demolished and the site is now a parking lot. The family moved to Michigan in 1930. Sandburg won the 1940 Pulitzer Prize for History for the four-volume The War Years, the sequel to his Abraham Lincoln, and a second Poetry Pulitzer in 1951 for Complete Poems. In 1945 he moved to Connemara, a 246-acre (100 ha) rural estate in Flat Rock, North Carolina. Here he produced a little over a third of his total published work and lived with his wife, daughters, and two grandchildren.

On February 12, 1959, in commemorations of the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's birth, Congress met in joint session to hear actor Fredric March give a dramatic reading of the Gettysburg Address, followed by an address by Sandburg. Sandburg supported the Civil Rights Movement and was the first white man to be honored by the NAACP with their Silver Plaque Award as a major prophet of civil rights in our time. Sandburg died of natural causes in 1967 and his body was cremated. The ashes were interred under "Remembrance Rock", a granite boulder located behind his birth house in Galesburg.

Rootabaga Stories (book 1, 1922). Sandburg rented a room and lived for three years in this house, where he wrote the poem "Chicago". It is now a Chicago landmark. Much of Carl Sandburg's poetry, such as "Chicago", focused on Chicago, Illinois, where he spent time as a reporter for the Chicago Daily News and the Day Book.Sandburg earned Pulitzer Prizes for his collection The Complete Poems of Carl Sandburg, Corn Huskers, and for his biography of Abraham Lincoln (Abraham Lincoln: The War Years). [15] Sandburg is also remembered by generations of children for his Rootabaga Stories and Rootabaga Pigeons, a series of whimsical, sometimes melancholy stories he originally created for his own daughters.

He felt that the European stories involving royalty and knights were inappropriate, and so populated his stories with skyscrapers, trains, corn fairies and the "Five Marvelous Pretzels". In 1919, Sandburg was assigned by his editor at the Daily News to do a series of reports on the working classes and tensions among whites and African Americans. The impetus for these reports were race riots that had broken out in other American cities. Ultimately, major riots broke out in Chicago too, but much of Sandburg's writing on the issues before the riots caused him to be seen as having a prophetic voice.

A visiting philanthropist, Joel Spingarn, who was also an official of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, read Sandburg's columns with interest and asked to publish them, as The Chicago Race Riots, July, 1919. Sandburg's popular multivolume biography Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years, 2 vols. (1926) and Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, 4 vols. [23] The books have been through many editions, including a one-volume edition in 1954 prepared by Sandburg. Sandburg's Lincoln scholarship had an enormous impact on the popular view of Lincoln.

The books were adapted by Robert E. Sherwood for his Pulitzer Prize-winning play Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1938) and David Wolper's six-part dramatization for television, Sandburg's Lincoln (1974). He recorded excerpts from the biography and some of Lincoln's speeches for Caedmon Records in New York City in May 1957.

He was awarded a Grammy Award in 1959 for Best Performance Documentary Or Spoken Word (Other Than Comedy) for his recording of Aaron Copland's Lincoln Portrait with the New York Philharmonic. Some historians suggest more Americans learned about Lincoln from Sandburg than from any other source. The books garnered critical praise and attention for Sandburg, including the 1940 Pulitzer Prize for History for the four-volume The War Years. But Sandburg's works on Lincoln also brought substantial criticism. Barton, who had published a Lincoln biography in 1925, wrote that Sandburg's book "is not history, is not even biography" because of its lack of original research and uncritical use of evidence, but Barton nevertheless thought it was real literature and a delightful and important contribution to the ever-lengthening shelf of really good books about Lincoln. [25] Others criticized Sandburg's failure to document sources and factual errors.[23] Others complain The Prairie Years and The War Years contain too much material that is neither biography nor history and is instead "sentimental poeticizing" by Sandburg. [23] Sandburg may have viewed his book as an American epic more than as a mere biography, a view mirrored by other reviewers as well. Sandburg's 1927 anthology, the American Songbag, enjoyed enormous popularity, going through many editions; and Sandburg himself was perhaps the first American urban folk singer, accompanying himself on solo guitar at lectures and poetry recitals, and in recordings, long before the first or the second folk revival movements (of the 1940s and 1960s, respectively). [26] According to the musicologist Judith Tick.

As a populist poet, Sandburg bestowed a powerful dignity on what the'20s called the "American scene" in a book he called a ragbag of stripes and streaks of color from nearly all ends of the earth... Rich with the diversity of the United States. Reviewed widely in journals ranging from the New Masses to Modern Music, the American Songbag influenced a number of musicians. Pete Seeger, who calls it a "landmark", saw it almost as soon as it came out. " The composer Elie Siegmeister took it to Paris with him in 1927, and he and his wife Hannah "were always singing these songs.That was where we belonged. Sandburg said he considered working on D. Griffith's Intolerance (1916) but his first film work was when he signed on to work on the production of The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) in July 1960 for a year, receving an "in creative association with Carl Sandburg" credit on the film. Carl Sandburg's boyhood home in Galesburg is now operated by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency as the Carl Sandburg State Historic Site.

The site contains the cottage Sandburg was born in, a modern visitor's center, and small garden with a large stone called Remembrance Rock, under which his and his wife's ashes are buried. [29] Sandburg's home of 22 years in Flat Rock, Henderson County, North Carolina, is preserved by the National Park Service as the Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site. Sandburg on historical roots, displayed at Deaf Smith County Museum, Hereford, TX. On January 6, 1978, the 100th anniversary of his birth, the United States Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp honoring Sandburg. The spare design consists of a profile originally drawn by his friend William A.Smith in 1952, along with Sandburg's own distinctive autograph. The Rare Book & Manuscript Library (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) (RBML)[31] houses the Carl Sandburg Papers. In total, the RBML owns over 600 cubic feet of Sandburg's papers, including photographs, correspondence, and manuscripts. In 2011, Sandburg was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.

Carl Sandburg Village was a 1960s urban renewal project in the Near North Side, Chicago. Financed by the city, it is located between Clark and LaSalle St. Between Division Street and North Ave. In 1979, Carl Sandburg Village was converted to condominium ownership. Numerous schools are named for Sandburg throughout the United States, and he was present at some of these schools' dedications.[citation needed] Sandburg Halls, a student residence hall at the University of WisconsinMilwaukee, carries a plaque commemorating Sandburg's roles as an organizer for the Social Democratic Party and as personal secretary to Emil Seidel, Milwaukee's first Socialist mayor. Carl Sandburg Library opened in Livonia, Michigan in 1961.

The name was recommended by the Library Commission as an example of an American author representing the best of literature of the Midwest. Carl Sandburg had taught at the University of Michigan for a time. Galesburg opened Sandburg Mall in 1975, named in honor of Sandburg. The Chicago Public Library installed the Carl Sandburg Award, annually awarded for contributions to literature. A subdivision in a suburbs of Atlanta Georgia is named after Carl Sandburg and his life. Connemara HOA in Lawrenceville (GA) includes the namesake of Connemara, his home in NC. Street names include Galesburg Dr (his birthplace), Windflower Way (named after the poem Windflower Leaf), Remembrance Trace (named after his only novel of Remembrance Rock), Flat Rock Dr (his home of Connemara in Flat Rock, NC), and Lombard Dr (the College he attended). Amtrak added the Carl Sandburg train in 2006 to supplement the Illinois Zephyr on the ChicagoQuincy route.This article appears to contain trivial, minor, or unrelated references to popular culture. Please reorganize this content to explain the subject's impact on popular culture, providing citations to reliable, secondary sources, rather than simply listing appearances. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Find sources: "Carl Sandburg" news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message). Avard Fairbanks produced Sandburg's portrait during the Lincoln Sesquicentennial.It was cast in bronze and placed at the Chicago Historical Museum and at Knox College, his alma mater, in Galesburg, IL. Carl Sandburg portrait sculpture by Avard T. NBC produced a six-episode miniseries entitled Lincoln, also referred to as Carl Sandburg's Lincoln, starring Hal Holbrook and directed by George Schaefer, aired between 1974 and 1976. Richard Armour's poem "Driving in a Fog; or Carl Sandburg Must Have Been a Pedestrian" was published in the January 1953 Westways.

William Saroyan wrote a short story about Sandburg in his 1971 book, Letters from 74 rue Taitbout or Don't Go But If You Must Say Hello To Everybody. Thomas Hart Benton painted a portrait Carl Sandburg in 1956, for which the poet had posed. Sandburg's "Sometime they'll give a war and nobody will come" from The People, Yes was a slogan of the German peace movement ("Stell dir vor, es ist Krieg, und keiner geht hin"); however, it is often attributed to Bertolt Brecht. Daniel Steven Crafts' The Song and The Slogan is an orchestral composition built around recited passages from Sandburg's "Prairie".

Dan Zanes's Parades and Panoramas: 25 Songs Collected by Carl Sandburg for the American Songbag. Peter Louis van Dijk's "Windy City Songs", based on the Chicago poems, was performed by the Chicago Children's Choir and the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Choir in 2007. Steven Spielberg claimed that the face of E. Was based on a composite of Sandburg, Ernest Hemingway, and Albert Einstein.

Bob Gibson's "The Courtship of Carl Sandburg", starring Tom Amandes as Sandburg[41]. In Jonathan Lethem's novel Dissident Gardens the main character Rose Zimmer became an Abraham Lincoln devotee after reading Sandburg's biography. Her copy of the six volumes became the centerpiece of her shrine to Lincoln. Sufjan Stevens's Come on!

Part I: The Columbian Exposition Part II: Carl Sandburg Visits Me in a Dream (from Illinois). Main article: Carl Sandburg bibliography. In Reckless Ecstasy (1904) (poetry) (originally published as Charles Sandburg). Incidentals (1904) (poetry and prose) (originally published as Charles Sandburg). Plaint of a Rose (1908) (poetry) (originally published as Charles Sandburg).

Joseffy (1910) (prose) (originally published as Charles Sandburg). You and Your Job (1910) (prose) (originally published as Charles Sandburg). Chicago Race Riots (1919) (prose) (with an introduction by Walter Lippmann).

Clarence Darrow of Chicago (1919) (prose). Smoke and Steel (1920) (poetry). Rootabaga Stories (1922) (children's stories). Slabs of the Sunburnt West (1922) (poetry). Rootabaga Pigeons (1923) (children's stories). Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years (1926) (biography). The American Songbag (1927) (folk songs)[43][44]. Songs of America (1927) (folk songs) collected by Sandburg; edited by Alfred V. Abe Lincoln Grows Up (1928) (biography [primarily for children]).Good Morning, America (1928) (poetry). Steichen the Photographer (1929) (history). Potato Face (1930) (children's stories). Mary Lincoln: Wife and Widow (1932) (biography). The People, Yes (1936) (poetry).

Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (1939) (biography). Storm over the Land (1942) (biography) (excerpts from Sandburg's own Abraham Lincoln: The War Years). Road to Victory (1942) (exhibition catalog) (text by Sandburg; images compiled by Edward Steichen and published by the Museum of Modern Art). Home Front Memo (1943) (essays). Lincoln Collector: the story of the Oliver R.

Barrett Lincoln collection (1949) (prose). The New American Songbag (1950) (folk songs). The Wedding Procession of the Rag Doll and the Broom Handle and Who Was In It (1950) (children's story). Always the Young Strangers (1953) (autobiography). Selected Poems of Carl Sandburg (1954) (poetry) (edited by Rebecca West).The Family of Man (1955) (exhibition catalog) (introduction; images compiled by Edward Steichen). Prairie-Town Boy (1955) (autobiography) (essentially excerpts from Always the Young Strangers). Sandburg Range (1957) (prose and poetry).

Harvest Poems, 19101960 (1960) (poetry). The World of Carl Sandburg (1960) (stage production) (adapted and directed by Norman Corwin, dramatic readings by Bette Davis and Leif Erickson, singing and guitar by Clark Allen, with closing cameo by Sandburg himself). Carl Sandburg at Gettysburg (1961) (documentary). Honey and Salt (1963) (poetry). The Letters of Carl Sandburg (1968) (autobiographical/correspondence) (edited by Herbert Mitgang).Breathing Tokens (poetry by Sandburg, edited by Margaret Sandburg) (1978) (poetry). Ever the Winds of Chance (1983) (autobiography) (started by Sandburg, completed by Margaret Sandburg and George Hendrick).

Carl Sandburg at the Movies: a poet in the silent era, 19201927 (1985) (selections of his reviews of silent movies; collected and edited by Dale Fetherling and Doug Fetherling). Billy Sunday and other poems (1993) (edited with an introduction by George Hendrick and Willene Hendrick). Poems for Children Nowhere Near Old Enough to Vote (1999) (compiled and with an introduction by George and Willene Hendrick). (1999) 73 newfound poems from his early years in Chicago, edited with an introduction by George Hendrick and Willene Hendrick. Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years (2007) (illustrated edition with an introduction by Alan Axelrod).The item "AWESOME CARL SANDBURG HANDWRITTEN POEM AND ARTWORK VERY RARE DETROIT CARTOONIST" is in sale since Thursday, June 10, 2021. This item is in the category "Collectibles\Autographs\Historical". The seller is "collectiblecollectiblecollectible" and is located in Ann Arbor, Michigan. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, South Korea, Indonesia, Taiwan, South africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi arabia, Ukraine, United arab emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Croatia, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa rica, Panama, Trinidad and tobago, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman islands, Liechtenstein, Sri lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macao, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Paraguay, Reunion, Viet nam, Uruguay.