- Poems Poetry Art

- Binding

- Listed By

- Signed

- Style

- 1940-1960 (6)

- Abstract (81)

- Art Deco (4)

- Art Nouveau (8)

- Asian (55)

- Contemporary Art (14)

- Expressionism (6)

- Folk Art (6)

- Impressionism (11)

- Minimalism (14)

- Modern (10)

- Modernism (20)

- Modernist (3)

- Pop Art (11)

- Portrait (7)

- Realism (15)

- Surrealism (15)

- Traditional (11)

- Urban Art (9)

- Vintage (16)

- ... (2453)

- Subject

- Abstract (48)

- Art (25)

- Art & Photography (219)

- Art And Poetry (6)

- Calligraphy (29)

- Children's (9)

- Conceptual Art (9)

- Figures (19)

- Figures & Portraits (21)

- History (15)

- Illustrated (25)

- Landscape (22)

- Literature & Fiction (175)

- Performing Arts (44)

- Philosophy (6)

- Poem (14)

- Poems (6)

- Poetry (66)

- Portrait (10)

- Quote (14)

- ... (1993)

- Type

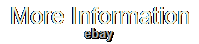

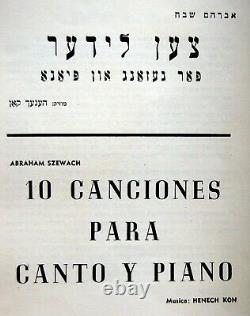

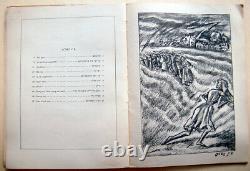

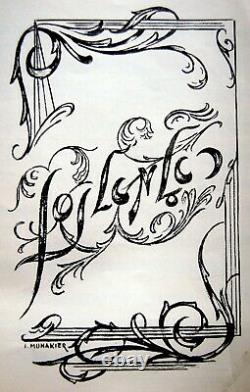

Jewish YIDDISH SONGS Poems HOLOCAUST ART BOOK Composer HENECH KON Piano JUDAICA

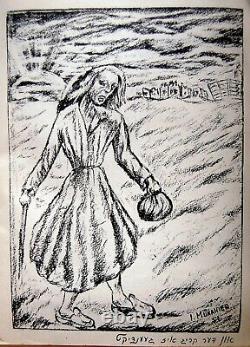

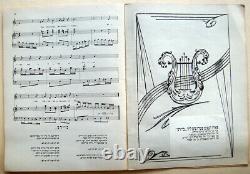

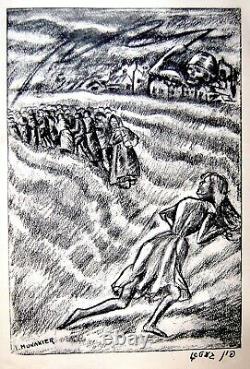

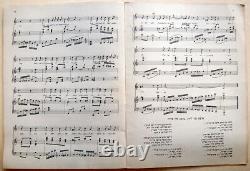

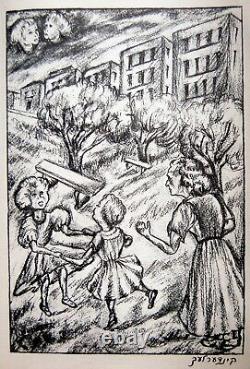

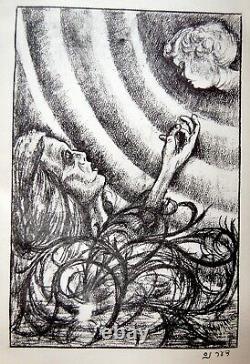

With full 10 MUSICAL NOTES. Not much is known on the JEWISH POET of Polish Bialystok descent - ABRAHAM SZEWACH (Also AVROM SHEVEKH - SHEWACH) who was born in BIALYSTOK , But lived also in ERETZ ISRAEL - PALESTINE and BUENOS AIRES and even less is known about the Jewish painter ISAAC MUNAKIER who contributed a few HOLOCAUST RELATED ART LITHOGRAPHS to this UNIQUE PUBLICATION. Much morte is known about the acclaqimed Jewish COMPOSER of these 10 SONGS - HENECH KON.

KON , of LODZ POLISH descent. A composer of musical theatre, was an important member of the thriving inter-war Polish-Jewish cultural scene. He wrote popular songs, and participated in a wide variety of cultural activities for Jewish and non-Jewish Poles. Henech Kon is best known today as the composer of the film score for.

And his songs, such as Shpil zhe mir a lidele in Yidish. He was, however, also a brilliant pianist and musicologist, and wrote arrangements for dozens of Yiddish songs and other scores, among them. Born in Poland and educated in Berlin, he moved to Warsaw where he worked with the great writers of his time, and wrote music for their plays and. Melech Ravitch called him the Jewish musician par excellence.

A few FULL PAGE drawings , Printed as issued on one face only of the leaf. The book is EXTREMELY RARE and impossible to find. (Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images). Book will be sent inside a protective packaging. Henech Kon or Henryk Kon (9 August 1890 20 April 1972)[1] was a Polish composer and cabaret performer. Kon was born in ód to a Chassidic family, and sent at the age of 12 to his grandfather in Kutno, where he studied Torah but also studied with local klezmers, absorbing folk music from players and badkhonim. [2] When his family realized he would never be a rabbi, they sent him to music school in Berlin. Her then husband, sculptor Bernard Kratko, introduced Kon to Isaac Leib Peretz and Kon set several of Peretz's works to music, including Treyst mayn folk (Comfort My People) and the play Bay nakht oyfn alten mark (A Night in the Old Marketplace). In 1922 proletarian Lodz was tired of earnest dramas and light comedies. [2] Responding to the new popularity of satire, Kon with poet Moishe Broderzon and painter Yitschok Broyner created the marionette theater Chad-Gadya, the first of a string of revi-teaters (venues for music theater revues) in Polish towns and cities. Henekh Kon was Moyshe Broderson's closest collaborator, building with him all the kleynkunst theaters in Poland: the marionette-theater Khad-Gadye (1922) in Lodz, the kleynkunst theater Azazel (1925) in Warsaw, Sambatiyon (1926) and Ararat (1927). His was the musical spirit behind all of them.[3] He later was also closely associated with the kleynkunst (small art) venue Ararat. He composed music for around 40 theater productions, [4] including Sholem Asch's Kiddush ha-Shem, Shakespeare's Shylock, Aaron Zeitlin's (Tseytlin's) Yidnshtot, Moshe Lipshitz' Hershele Ostropolyer, Dovid Bergelson's Di broytmil (The Bread Mill), H. Leyvik's Der Golem, and many others. His opera David and Batsheba was written (with Moishe Broderzon) and presented in Warsaw in 1924, in a piano version.

Kon himself sang in the production, as did Moshe Shneur's chorus. Ninety-five years later, the orchestral version was created in Weimar, on 16 August 2019, during the Yiddish Summer Weimar Festival. [5] He is strongly associated with the Warsaw Yung-teater, [6] the Yiddish avant-garde theater company which emerged from Michal Weichert's Yiddish Theater Studio. He wrote the music for Boston, about Sacco and Vanzetti, Trupe Tanentzap, an Abraham Goldfaden spectacle, Napoleon's Treasure, based on a Sholem Aleichem story, and many others. After the Second World War Henoch Kon worked with the Yiddish Art Theater in Paris.

Beginning in 1934 he also worked in film; he composed the music for The Dibbuk and Zygmunt Turkow's Di freylekhe kabtsonim (The Jolly Paupers), among others. He moved to America, where he was never particularly successful, [7] and died in New York City. Isaac Munakier AVROM SHEVEKH (ABRAHAM SZEWACH) AVROM SHEVEKH (ABRAHAM SZEWACH) (August 15, 1904-April 20, 1969) He was a poet, born in Bialystok. He attended Yafes shule (Yafes school) in Bialystok. In 1930 he emigrated to Argentina, where he took up business.

In early 1969 he made aliya to Israel. He died en route and was buried in Buenos Aires. He began writing poetry in Yiddish while quite young, and later used Esperanto. He published in: Byalistoker shtime (Voice of Bialystok); and Byalistoker vegn (Bialystok ways), Di prese (The press), and Idishe tsaytung (Jewish newspaper), among other serials, in Buenos Aires.

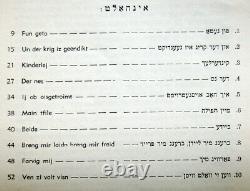

His work appeared as well in: V. Bresler, Antologye fun der yidisher literatur in argentine (Anthology of Jewish literature in Argentina) (Buenos Aires, 1944); Zamlbukh (Collection) of the H. Nomberg Writers Association in Argentina (Buenos Aires, 1962); Shmuel Rozhanski, ed. Khurbn, antologye 109 poetn, dertseylers un memuaristn (Holocaust, anthology of 109 poets, short story writers, and memoirists) (Buenos Aires, 1970). In book form: Tsayt-lider (Topical poetry) (Buenos Aires, 1944), 32 pp. Ten lider far gezang un pyano (Ten poems for singing and piano), music by Henekh Kon (Buenos Aires: Association of Fellow Bialystok Natives in Argentina, 1952), 52 pp. Abraham Szewach urodzi si 15 sierpnia 1904 r. W Biaymstoku, gdzie uczszcza do szkoy Yafes Shule. Zosta pisarzem, dziennikarzem i poet. Pisa dla Byalistoker shtime (Gos Biaegostoku) oraz Byalistoker vegn (Biaostockie drogi). Wyemigrowa do Argentyny, pisa w Buenos Aires do Di prese (Prasa), a take dla Idishe tsaytung (Gazeta ydowska) i in. Jego prace znalazy si równie w zbiorach V. Bresler, Antologye fun der yidisher literatur in argentine (Analogia literatury ydowskiej w Argentynie) (Buenos Aires, 1944); Zamlbukh (Colekcja) wydana przez H. Khurbn, antologye 109 poetn, dertseylers un memuaristn (Holocaust, antologia 109 poetów, pisarzy nowel i pamietników) (Buenos Aires, 1970), In book form: Tsayt-lider (Topikalna poezja) (Buenos Aires, 1944), 32 pp. Ten lider far gezang un pyano (10 wierszy na gos i pianino), muzyka Henekh Kon (Buenos Aires: Association of Fellow Bialystok Natives in Argentina, 1952). W latach cztyerdziestych XX w. W Buenos Aires pisa ydowskie tanga dla teatrów rewiowych, takich jak Mitre, gdzie dyrygentem by inny biaostoczanin Jeremias Ciganeri. Do kompozycji Ciganeriego Szewach napisa m in. Teksty utworów: Bialystok mayn heym (Biaystok mój dom), Bialystoker geselakh (Uliczki Biaegostoku), Vu iz dayn shmeykhl? , Far mentshn bin ikh freylekh (Ludzie widz mnie szczliwym), Ikh vel laydn in der shtil (Bd cierpia w ciszy). Abraham Shewach was born on August 15, 1904 in Bialystok, where he attended yafes shule school. He became a writer, journalist and poet. He wrote for Byalistoker shtime (Voice of Bialystok) and Byalistoker vegn (Bialystock roads). In 1930 he emigrated to Argentina, wrote in Buenos Aires do Di prese (Press), as well as for Idishe tsaytung (Jewish Newspaper) and others. His works were also included in the collections of V. Bresler, Antologye fun der yidisher literatur in argentine (Analogy of Jewish Literature in Argentina) (Buenos Aires, 1944); Zamlbukh (Colekcja) published by H. Nomberg Writers' Association in Argentina (Buenos Aires, 1962); Shmuel Rozhanski, ed. Khurbn, antologye 109 poets, dertseylers un memuaristn (Holocaust, anthology of 109 poets, novel writers and mementists) (Buenos Aires, 1970), In book form: Tsayt-leader (Topikalna poetry) (Buenos Aires, 1944), 32 pp. This leader far gezang un pyano (10 poems aloud and piano), music by Henekh Kon (Buenos Aires: Association of Fellow Bialystok Natives in Argentina, 1952). In the 1940s, in Buenos Aires, he wrote Jewish tangos for revue theatres such as Mitre, where another white-stochanin Jeremias Ciganeri was the conductor. For the composition of Ciganeri Szewach wrote, among others, lyrics of songs: Bialystok mayn heym (Bialystok my house), Bialystoker geselakh (Streets of Bialystok), Vu iz dayn shmeykhl? , Far mentshn bin ikh freylekh (People see me happy), Ikh a. Laydn in der shtil (I will suffer in silence). Kon Henoch (09.08.1890 ód 20.04.1972 Nowy Jork) kompozytor. Kon urodzi si w rodzinie ydowskiej w odzi. Ksztaci si w Królewskiej Wyszej Szkole Muzycznej w Berlinie. Mieszka i pracowa w Warszawie. Przyjani si z Icchokiem Lejbem Perecem. Napisa muzyk do jego utworów Baj nacht ojfn altn markt jid. Noc na starym rynku i Trajst majn folk jid. W okresie midzywojennym aktywnie uczestniczy w yciu artystycznym Warszawy.Pracowa jako kierownik muzyczny i kompozytor muzyki dla teatrów ydowskich, m. Dla Warszewer Jidiszer Kunst-Teater jid. Warszawski ydowski Teatr Artystyczny, Chad Gadjo, teatru Ararat, teatru Azazel oraz Jung Teater. Napisa oper Dawid i Batszewa do libretta Mojesza Brodersona, wystawionej w 1924 r.

Napisa te muzyk do ok. Der Gojlem Halpera Lejwika, Shylocka wedug Williama Szekspira, Kidusz Ha-Szem Szaloma Asza, Cwej hundert tojznt Szolema Alejchema oraz filmów. Jego muzyk mona usysze w filmach jidysz wyprodukowanych w latach 30.

W Polsce Mir kumen on (1934), Al chet (1936), Dybuk (1937), Frejleche kabconim (1937). Tu przed wybuchem II wojny wiatowej Kon wyjecha do Stanów Zjednoczonych. Ydowski Teatr Artystyczny Maurice'a Schwartza. Po wojnie opracowa zbiór pieni z czasów Zagady, który wydano pt. Lider fun geto un widersztand.

Film ydowski w Polsce, Kraków 2002. Tlomackie 13, Buenos Ajres 1946. Ha-Muzika ha-jehudit we-jocreha, Tel Awiw 1960. Negine in jidiszn lebn, Toronto 1957. Farloszene sztern, Buenos Aires 1953.Di ibergerisene tkufe, Buenos Aires 1961. Zichrojnes, 2 Bd: Warsze, Tel Awiw 1961. Kleynkunst Contents Hide Suggested Reading Author Translation A genre of Yiddish performance, kleynkunst (little art; also known as minyatur teater [miniature theater]) developed in the early twentieth century, primarily under the influence of Russian and Polish literary cabaret.

The genre was also indebted to older forms of Yiddish performance, that of purim-shpilers and badkhonim, as well as to the nineteenth-century semiprofessional performers known as the Broder Singers. Rooted in traditional Jewish societies, such performers nevertheless subjected the Jewish community and its leadership to merciless parody while exposing a range of injustices. Integrating song and dance with sketches and routines of various kinds, kleynkunst satirized both Jewish society and the political and social order of the non-Jewish world, especially its impact on Jews. Kleynkunst aspired to contemporary relevance even as it reflected everyday Jewish life and traditions.

The names of kleynkunst companies, for example, were often linked to Jewish folkore: Azazel, mentioned in the Bible, is associated with the demonic, as is Ararat, the biblical location of Noahs ark (though the name was also an acronym for Artistisher Revolutsyonerer Revi-Teater [Artistic Revolutionary Revue-Theater]); Sambatyon is the name of a river of stones beyond which the 10 lost tribes were said to live. One of the first companies that could be termed kleynkunst began to perform during World War I. It consisted of a group of professional variety performers assembled by Solomon Kustin (18781949), who had performed Yiddish vaudeville in America, and his wife, Sonia Kompanyeyets. The troupe, including Peysekh Burshteyn (Burstein; 19001986) and Hersh Yedvab (Jedwab; 18701931), performed one-act plays, monologues, and off-color songs, but also included political numbers.

The first Yiddish literary or artistic kleynkunst performances were satirical musical reviews, which the poet and dramatist Yankev Shternberg staged in his own theater in Bucharest in 19171918. The first kleynkunst company in Poland, where the genre flourished, was Azazel, organized in Warsaw in 1925 by a group that included Totshe Artsishevski (Tea Arciszewska) and Dovid Herman (director of Der dibek), who had been disciples of Y.

Peretz; as well as the painter Henryk Berlewi, the composer Henekh Kon, and other young artists and writers. Azazel included amateurs, Hermans students, and professionals, among them, Wadysaw Godik (18921952), who served as master of ceremonies; Khayim Sandler 1886194? ; and Yosef Strugatsh Strugacz; 1893?

Azazel made use of texts by Peretz and Sholem Aleichem as well as contemporary material written by Moyshe Broderzon, Itsik Manger, Alter Kacyzne, Y. Nayman, Der Tunkeler (Yoysef Tunkel), Yankev Oberzhanek (18911943), and Moyshe Nudelman 1905? The cabaret quickly became very popular, especially among artists and intellectuals, Jewish and occasionally Polish as well. The latter was related to efforts by Warsaw police to rid the streets of unlicensed bagel vendors. By 1927, however, financial difficulties forced the company to go on tour and to disband soon after.

Short skits by the famous Kleynkunst [cabaret] theater! Polish/Yiddish poster, artwork by Kultura, printed by M. (YIVO) In ód, the avant-garde poet Moyshe Broderzon organized Ararat in 1927, modeled upon Azazel. Broderzon, who wrote much of the material himself, was a master of wordplay who created striking puns and rhymes. Much of the material reflected local issues and was performed in the ód dialect of Yiddish and not in the southeastern vernacular common to the Yiddish stage. Broderzon relied principally on young amateur performers whose talent he was quick to recognize. These included Shimen Dzigan and Yisroel Shumacher, the future comedy team; the comedian Shmulik Goldshteyn 1908?; the actress Menukhe Bernholts (later known as Mina Bern, who was still performing Yiddish theater in New York 70 years later); and Iza Harari, who would gain renown as the dancer and choreographer Judith Berg. Dzigan and Moyshe Pulaver 1902? Were Ararats stage directors, Henryk Jablon and Henekh Kon its musical directors, Yitskhok Broyner (18891944) and Roman Rozental 1897194? Ararat also developed a following of loyal fans who clung to Broderzon like Hasidim to their rebbe Nudelman, 1968, p.

155; some even copied his idiosyncratic style of dress. Gradually, personal rivalries and financial difficulties caused splits in Ararat, but it continued to perform with changing personnel throughout Poland in the 1930s and in 1935 toured Western Europe.

Sambatyon was established in Vilna in 1926 but moved to Warsaw several months later. It was made up exclusively of professional performersYitskhok Feld, Khane Grosberg 1900? , Khayim Sandler, and othersunder the direction of the actor and director Yitskhok Noyk 1889? , who also wrote much of the material; other writers included Der Tunkeler, Der Lustiker Pesimist (Yosef Shimen Goldshteyn), Moyshe Nudelman, S. , and Bontshe (Avrom Rozenfeld; 18841941/42). Noyk aimed to offer a popular audience an alternative to American Yiddish and European operetta fare, staging well-known Yiddish songs and writing comical and melodramatic sketches. But Sambatyon also performed more literary and experimental material; for several months, the poet Yisroel Shtern was its literary director. Under various names and with varying personnel, the company performed in Warsaw and toured Poland until the end of 1929, when it disbanded. Di Yidishe Bande (The Jewish Gang) began in Kalisz in 1932, then moved to ód and Warsaw and toured Poland until World War II.Its name was an allusion to a popular Polish cabaret known as Banda (The Gang). Consisting exclusively of professional performers, Di Yidishe Bande aspired primarily to entertainment. Its directors were the actors Dovid Lederman and Zishe Kats 1892194? ; other performers included Khane Grosberg and Ayzik Rotman.

In the last years before World War II, Dzigan and Shumacher established a kleynkunst troupe at the Teatr Nowoci in Warsaw. During the interwar years, there were also other cabarets in Poland with a more local following. These included Gilarina in Biaystok, Moloditsa in Bielsk, Simkhevesosn in Grodno, and Davke in Vilna.

In addition, two puppet theaters staged sophisticated satirical productions in the kleynkunst manner. These were Khad-gadye, which came to ód from Warsaw, created by Moyshe Broderzon, Henekh Kon, and Yitskhok Broyner in the early 1920s, and Maydim, the creation of Aron Bastomski (19071944) and a collective of writers, musicians, and artists in Vilna from 1933 to 1942. Unlike many refugee composers and other artists from the Third Reich (German-occupied lands as well as Germany or Austria), who, despite the trauma of transplantation, were fortunate in reestablishing themselves in America, Henoch Kon appears to have been unable to reconstruct the visible and fruitful career he enjoyed in prewar Poland. Owing to the dearth of extant primary sources, as well as his relative obscurity in America, we are heavily (though not exclusively) reliant on the accounts and assessments offered and quoted by Issachar Fater, the most thorough chronicler of Jewish musical life in interwar Poland.

Born in ód, Poland, to a Hassidic-oriented family, Kon was sent at age twelve to Kutno (birthplace of the famous Yiddish writer and playwright Sholem Asch, 18801957), to be reared in the home of his grandfather, Rabbi Hayyim Moshe Lipsky, who supervised the boys religious studies in the hope of his becoming a Torah scholar. But Kon succumbed to the lure of the muse. Perhaps more than might have been the case in relatively diverse ód, he was exposed in Kutno to the music of klezmorim and badkhonim. He was increasingly drawn to their folk-derived modes, melodies, and other materials, which sparked his desire to study music on a serious level in order to incorporate those traditions within cultivated forms.

Eventually his parents acquiesced in his determination to pursue music as his principal focus. Abandoning the yeshiva world and the Hassidic life of his grandfather, he went to Berlin, where he studied for a few years at the Royal Academy of Music (Königliche Hochschule für Musik). Upon his return, Kon was initiated into the Yiddish literary and artistic circles of Jewish Warsaw. He became a frequent visitor to the salons of the actress Thea Artsishevska [Miriam Izrales], whose former husband, the sculptor B.

Kratka, introduced him to the famous Yiddish writer, poet, and playwright Isaac Leyb [Yitskhoh Leyb/Leybush] Peretz. Kon soon became a regular guest at Peretzs Sabbath-afternoon gatherings. He was especially attracted to Peretzs writings and was inspired to develop a means of expressing them in music.Kon wrote music for Peretzs Treyst mayn folk (Console My People), An edom (An Edomite), Sshlaykht tsu a shtot di shverd bay nakht, and other works; and years later he composed a score for Peretzs play Bay nakht afn alten mark (At Night in the Old Market). Peretz is said to have been so impressed that he told Kon, If you dont do it [create music for my work], no one will. Kon came to consider Peretz his mentor with regard to Yiddish literature, and he took Peretzs charge as a personal artistic responsibility. It was through Peretzs influence, according to Fater, that Kon became devoted to Yiddish theater in Poland.

Beginning in 1922, he joined with two contemporaries in the development and advocacy of Yiddish theater in ód. His partners were the painter Yitzhak Broyner, and Moshe Broderzonthe Yiddish poet, journalist, theater director, and playwright who headed the literary society Yung-yidish and is credited with discovering and promoting many talented candidates for the Yiddish stage.Fater tells us that the proletarian audiences in ód, weary of serious drama (including comedies) and eager for a lighter variety of humor and satire, were receptive to Borderzons founding of Khad Gadyo, the first Yiddish marionette theater, in which Kon played an important musical role. He also contributed to other small repertory art theaters in ód that were founded by Broderzon, such as Ararat and Shorabor, and Azazel in Warsaw, cofounded with Thea Artsishevska.

During that period, Kon composed songs and other musical numbers for about forty theatrical productions. Among his incidental music for Yiddish plays were scores for a number of productions of the famous Yiddish theatrical troupe from Vilna (Vilnius), the Vilner Truppe: Sholem Aschs Kiddush hashem (Sanctification of Gods Holy Name); Aaron Zeitlins Yidnshtot (A Jewish Town); Moshe Lipshitzs Hershele Ostropole, a variant of Shalom Aleichems Tsvey hundert toyznt; Y.

Aniels Shvartze geto; David Bergelsons Di broytmil; H. Leivicks [Leivick Halperin] Der golem; A. Tretiakovs Shray khine (Scream, China); and Shaylok, a Yiddish adaptation of Shakespeares The Merchant of Venice. Kon was even more intensely involved with the Yung Teater, which was directed by Dr. Mikhal Vaykhert and flourished until the German invasion of Poland in 1939. Kon conducted and wrote scores for its productions, which included Yakov Pragers Simkhe Plakhte; Napoleons Oytser (Napoleons Treasure), based on a play by Shalom Aleichem; Dos lebn ruft, an adaptation of a work by the American author Theodore Dreiser; Krasin, a play about the northern expedition of the Italian general Nobile; Trupe Tanantsop, billed as a Goldfaden Spectacle, with reference to Abraham Goldfaden (18401908), who founded modern Yiddish musical theater in Romania and is considered the father of the genre; Misisipi [Mississippi], a piece by Leib Malakh about the experience of American blacks; and Bostn [Boston], a play about the emotionally and politically charged Sacco and Vanzetti episode, which involved the widely considered unfair and prejudicial murder trial of two Boston-area Italian immigrant workers and avowed anarchistsand their 1927 executions following denials of their appeals for retrial. Reactions to that production were bound to be explosive, according Kon a heightened measure of local publicity, even if his contribution was confined to the musical score. The guilt or innocence (or the degree of complicity, if any) of Ferdinando Nicola Sacco, a shoemaker, and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, a fishmonger, in the 1920 robbery and murder of two pay clerks in South Braintree, Massachusetts, remains the subject of continued controversy. The question is not likely to be resolved, despite numerous attempts to revisit the evidence, including some that is said to have surfaced later.Sacco and Vanzetti were unrepentant and probably active followers of a deported anarchist leader who openly advocated violent revolution, including bombing and assassinations. But at the timewith respect to the particular crime with which they were charged, the mood of the trial, the reported behavior of the judge, and especially their death sentencesthey were perceived as victims of the hysteria surrounding a climate of anarchist violence and of anti-immigrant and anti-Italian bias. Vocal but ultimately unsuccessful lobbying for a retrial came not only from such responsible Socialist or left-leaning intellectuals and progressive thinkers as George Bernard Shaw, Upton Sinclair, Bertrand Russell, and H. Wells, but also from Felix Frankfurter, the future Supreme Court justice.

Vociferous protests both before and following the executions reverberated internationally, with demonstrations and even riots as far away as England, France, and Germany. The fact that the Yung Teater anticipated an audience for the playand that Kon was sufficiently interested to warrant his musical contributionsmay be further indication of the geographical breadth of the outcry of perceived injustice. It is also probably a measure of the empathy harbored by certain elements among Yiddish-speaking working classes in Poland. There are reports of riots in Warsaw surrounding the opening of the production; the few in America and Israel who were even familiar with Kons name by the end of the 20th century usually remembered it in connection with that incident. An interesting anecdote that offers insight into Kons modus operandi was recorded in the Warsaw Haynt in an article by the Yung Teaters director, Dr.

Vaykhert, who was also an arts and literature critic for that periodical. Vaykhert describes the initial frustration over Kons inaccessibility when it was first determined to produce the play Misisipi and a score had to be commissioned: Kon was then out of the country, so I turned to other musiciansamong them [the well-known folk bard Mark] Warshavsky. But as much as I tried to explain what I was seeking, no one was able to get it. So I wrote to Kon with a copy of the script and a description of what we had in mind for each musical number. No response for a long time. Then, ten days before the production, Kon showed up at the theater one morning with his completed music for the show under his arm. He sat down at the keyboard and played the music. We were stunned; we could not have had better! In 1924 Kon wrote an opera on the biblical story of David and Bathsheba, Dovid un bas sheva, to a libretto by Broderzon. From 1934 until he left Poland, Kon also wrote scores for a number of Yiddish films that were produced and shot there. The best known of these is Der dibuk, but others include Mir kumen on (We Are Arriving); his first film, Al kheyt; and Freylikhe kabtsonim. Fater presents Kon, during his Warsaw and ód years, as a true theater composerable to understand his role objectively as part of an organic whole and in the context of the nonmusical or extramusical parameters. In that spirit he tried to avoid writing songs or other musical numbers merely to fill gaps left by weaker moments in the action. Rather, his aim was to develop music that would contribute to a sustained, unified expression.Kon reflects the tale so honestly, wrote the poet, essayist, and critic Melech Ravitch [Zekharye Khone Bergnen (18931976)] years later, and tells it in so interesting a way that, at times, it seems that he should be a writer as well. Among writers he is the best musician; and among musicians he is the best writer. Nonetheless, some of the songs from Kons larger theatrical scores are said to have become popular as hits in their own right in interwar Poland, and even to have been sung as quasi-folksongs in Jewish homes: songs such as Loz mikh geyen du shlmazl (Let Me Go, You Hapless One), Oy vi sheyn (Oh, How Pretty), Yosl ber, and othersespecially those from his scores for Kiddush hashem; Parnose (material sustenance); and Hershele Ostropoler, about the legendary late-18th-century badkhn whose orally transmitted story has inspired many poems, plays, and even a novel. Ravitch later summed up Kons role in the Jewish cultural life of interwar Poland: We attempted to build a permanent and solid Jewish cultural life in Poland between the warsone that would be worldly as well as sacred to Jews. This was perhaps the first time that all elements and shades of Jewish life were combined to create a structure that would reflect a [composite] Jewish spiritual worldview.

Our aim was to create a worldly synagogue, a theater, a press, literature. And for the musical parameters, we turned to Henoch Kon.

Insofar as we know, Kon never composed for Hebrew liturgy or for the synagogue, nor was he involved directly in religious life. But Fater, who lived in Warsaw during the 1920s and 1930s and was an active participant in its Jewish cultural life as a musician and critic, observed that Kons theater music revealed the transparent influence of traditional [eastern] Ashkenazi synagogue melos; and a reverence for the Hassidic nign [melody] is evident throughout. It takes no guesswork to trace that affinity to his youthful familiarity with Hassidic environments. For Kon, the nign seems to have transcended Hassidism and religious connotations, representing an extra-religious associationa more generic singing of the folk. He looked consciously upon Hassidic melodies as a collective source on which to draw.

He is reported to have visited Hassidic shtiblekh (small prayer houses or synagogues) and attended Hassidic weddings expressly for this purpose. And he traveled to the town of Otwock (Otvotsk) near Warsaw to hear the Modzhitzer Rebbes (the spiritual leader of the Modzhitzer Hassidic dynasty) new dveikut lit. Clinging [to God]free-form Hassidic expressions of profound spiritual devotion, which, in general, are longer, more gradually and freely spun out, and less (if at all) metrically structured than niggunim. See the Introduction to Volume 6. After leaving Poland, Kon spent a short time in Paris, where he had some association with an émigré Yiddish art theater.

He also wrote about Jewish music for Yidn, a general encyclopedia in the Yiddish language that was published in Paris in 1940. Shortly afterward he immigrated to the United States and settled in New York. Over the next three decades he wrote many more individual songs; music for a cantata with a script by Wolf Younin, Gut yomtov yidn (Happy Holiday, Jews), to celebrate the tricentennial of American Jewry in 1954; and his last theater score (1963), for a play based on Chaim Grades 1955 Der mames shabosim (Mothers Sabbaths). He is known to have written, either in Europe or America, two ballets, choral settings, a few solo instrumental pieces, and some chamber musicnone of which seems to have gotten beyond the manuscript stage. Not all of this music is even extant.

A collection of Kons songs for voice and piano was published in New York in 1947, comprising eminently worthy settings of sixteen poems by some of the most respected serious Yiddish (and, in once case, Hebrew) poets: Peretz, Broderzon, ayyim Naman Bialik, Jacob Glatstein, Moshe Leyb Halperin, Zisha Weinper, Aaron Zeitlin, H. Kudlovitch, Abraham Liesin, Itzik Manger, Mani Leib, Daniel Charney, and Benjamin Jacob Bialostotzky.But it is not clear which if any of these songs were composed in Europe and which were written after his immigration to America. Separately, he wrote a set of twenty childrens songs, and another group of settings of poems by ten Yiddish poets who had been murdered by the Germans in Poland. During his first few years in New York, Kon did achieve some degree of recognition in Jewish music circles.

A concert devoted entirely to his compositions, for example, was presented in 1943 at the New School for Social Research. But that recognition soon faded, and in the postwar years his reputation rested mostly on his Holocaust-related songs. Only a few additional songs of lighter character, which gained some favor when they were performed by well-known recitalists, were published.In addition, his compilation Songs of the Ghetto was published in two volumes by the Congress for Jewish Culture (1960 and 1972), but these are his arrangements of songs that arose from, or were sung in, the German-built ghettos in occupied eastern Europe, rather than his own compositions. Kons published music represents only a fraction of his productivity. Over his lifetime he is believed to have written more than 150 songs.

The vast majority of thesewhether from his years in Poland (even including songs from his most successful theatrical scores) or from his American periodwere never published, and a great many have not been located. By all accounts, Kon never found a reliable means of adequate support in America, and it was an almost continual struggle to provide for himself.Relying on private charity and paltry sums from sales of individual songs in manuscript to singers whom he would implore to promote them, he appears to have lived in obscuritymuch of the time in the flat of a female painter friend, although the nature of their relationship is unclear. It was not unusual for him to sell a pencil manuscript of a song to a recognized singer, secure her promise to include it on a radio broadcast so that he could receive a tiny additional remuneration, and then borrow it back and resell itall out of desperation for subsistence.

Many of these songs may thus still reside among private papers, their identity yet to be discovered. Increasingly, Kon resorted to throwing together songs whose musical substanceas well as the quality of the lyricshe knew to be inferior, but whose minuscule compensation he needed. A group of amateur female would-be poets, for exampledubbed by a critic for the Yiddish daily Der Tog as di damen vos shraybn ramen (the ladies who write rhymes)would occasionally ask him to set their pedestrian poetry to music.

But he was paid only if they liked his setting or if the song was performed in public. Often he would have virtually to beg a professional singer to program the song as a personal favor, in order to assure the poetess of its value and thus receive remuneration. From stories such as these, from other isolated bits of information, and from interviews with people who had some passing contact with Kon in New York, a sad picture emerges of an artist who never recovered from the disruption of his rewarding, high-profile creative life in interwar Poland, nor from the upheaval of the Holocaust, in which many of his friends, colleagues, and family were slaughtered.

His American persona appears as a shadow of his former self and of his position in Polands cultural milieu. He is not known to have become involved with any American Yiddish cultural organizations or any American theatrical companies. Nor is there evidence that he made any attempts to revive his European activities in his new environment, for nowhere in related documents does his name appear. For more than three decades he remained a loner, almost to the point of reclusiveness. How much of that was caused by a purely psychological disorderperhaps an insurmountable depression that manifested itself only after 1940how much of it was the result of artistic disappointment, or how much of his eccentricity predated his immigration is impossible to know. Little about Kons personal life or personalityin Europe or America has come to light. By the time of his deathone day following his admission to the Bialystock Home for the Aged in New York, after he had been found by a retired singer incapacitated and half starved in an infested flathe had become virtually forgotten, even in Yiddish musical circles. Proper full evaluation of Kons talent and the qualitative merits of his music is necessarily incomplete and unfair without access to his prewar scores, which, if any are extant, have yet to be located and studied. We do not know how many he brought with him when he left Poland, nor how many might otherwise have vanished in the process of the German destruction of Polish Jewry.On the other hand, some of them might have reached Palestine in the hands of others and might now lie undiscovered and unexamined in archives or private collections in Israel. Some theater scores were left behind with their respective companies in Poland, especially ifas is often the case in the theater and commercial music worldthey had been considered works for hire that belonged contractually to those companies.

In any event, incidental theater music in general, like original orchestrations even for shows that attain major commercial success, are notorious for their disappearance following the runs of staged productions. His opera, however, resides in an American archive. Given the encomiums of praise that his music generated in ód and Warsaw, it is entirely possible that even the best of the songs Kon wrote in America do not, even as well-constructed miniatures (as in the 1947 collection devoted to serious poetry), reflect the full measure of his gifts. Yet those songs must not be dismissed. Certainly they exhibit taste, charm, musical wit, and artistic manipulation in their evocations of the poets moods and messages.

The piano parts, while breaking no new ground in their conventional tonality, transcend purely accompanimental roles, even if without bold adventure. They function with sufficient interdependence for the most part as the desired partners in a duo ensemble, which, in principle, is the desiderata of the art song (Kunstlieder) genre. And they provide pianistic interest within the confines of their intended immediacy. That these songs are infused at the same time with a refined folk characterrather than attaining the high art expression or the post-Romantic/post-19th-century sensibilities in the Yiddish art songs of a composer such as Lazar Weiner, who addressed many of the same poetsis at least in part a function of two entirely divergent approaches, considerations of the relative qualitative gifts of the composers aside.Kons chosen path in Europethe poets, playwrights, and other artists with whom he was associated, and the theatrical forces with which he aligned himselfsuggests that he considered himself a composer for those educated and culturally attuned Yiddish-speaking audiences whom he perceived as the folk. And it was on their appreciation of simply but artistically adorned folk styles and traditional flavors that he had learned to rely.

He probably did not view as his public the more classically oriented Jewish circles in Poland that were attracted, even if they were Yiddish speakers (in addition to Polish and/or German), to the Western musical canon. Even his opera, which, perhaps tellingly, was produced at the Kaminsky Theater and not at Warsaws principal opera house, was aimed at that urbanized folk more than at Jewish operagoers, whose desired operatic fare did not differ from that of non-Jewish patrons. It would be a disservice, therefore, to judge Kons music according to the standards of high art alone, or to dismiss it for its relative simplicity. Nonetheless, despite his respectably inventive treatment of the poetry in his 1947 art songs, there is about his American oeuvre a pervasive weariness that can seem at odds with the reported glory of his European phase. Whether this represents a decline in his inspiration or energies, whether he might have been misled by the popularity as well as commercial success of artistically wanting Yiddish songwriting in America, or whether the assessments of his work in Poland might have been exaggerated are questions that cannot be answered without comparative examination of the complete range of his music. Over the years, Kon also wrote many articles on Yiddish theater, music, and other topics for such Yiddish periodicals as Yung-yidish, Nayes Folksblat, Literarisher bletter, Der Forverts, and Moment. In the 1960s, despite his difficult circumstances in New York, Kon managed to visit Israel. He caused a minor stir at colloquiums there with his assertive defense of eastern European Jewish musical clichés and modes and his insistence on their perpetuation. For him, those elements were a necessary part of any fresh approach to a culturally inclusive Jewish national music.But many modern Israeli composers, critics, and others in the Israeli music establishment at that time considered his ideas reactionary, antiquated, andworst of allreliant on the music of exile. At an intimate gathering in Tel Aviv of literary and musical intellectuals, the Israeli music critic Menashe Ravina took issue with Kon on this matter, insisting that Kons preferred materials constituted a foreign source, inconsistent with the drive toward a modern Jewish musical language. Kon countered that he saw in those eastern European Jewish modalities not only a desired force for historical continuity but the combined mood of hope, faith, rebelliousness, and insubordination that had served the founders of the Jewish state well in their steadfastness against the opposition. Moreover, he maintained that all aspects of Jewish musical heritage should be represented: Our obligation is to take on the whole of Jewish musical tradition, he proclaimed, as it came down through the generations, and to protect its holiness.

Kon believed that the task of Jewish musicians should be to find a path to Jewish identity by drawing from traditionally Jewish sources of all kinds. He thought that was especially important for the older generations, for whom it would provide a connection to newer sounds. And he envisioned a new Jewish national music that would combine the musics of various Jewish traditions and communitiesAshkenazi modes, for example, blended with or juxtaposed against Yemenite Jewish tunes. When Fater met Kon in New York in 1968, Naomi Shemers famous song Yrushalayim shel zahav (Jerusalem of Gold)which, although written before the 1967 Six Day War, had become the virtual anthem of the war and its reunification of Jerusalemwas ubiquitous among world Jewry.

Unaware (as was everyone until Shemers deathbed confession more than twenty year later) that a part of it had been borrowed subconsciously from a Basque lullaby, Kon proclaimed it the beginning of a new era. HENECH KON A composer of musical theatre, Henech Kon was an important member of the thriving inter-war Polish-Jewish cultural scene. Ironically, as antisemitism began to increase in the 1930s, Jewish musical activity thrived, as entertainers began to lose their jobs elsewhere and were only able to find employment within the Jewish community. Kon was born in 1890 in ód, and as a boy of 12 was sent to live with his grandfather.He received a traditional Jewish education, and was also exposed to klezmer music, which influenced him to become a musician. Although his parents originally dreamed of his becoming a rabbi, they eventually agreed to support their sons musical aspirations. As a teenager he moved to Berlin, where he studied for several years at the Academy of Music.

He developed a friendship with the Yiddish writer I. Peretz, and later composed music to Peretz poems.

He was also drawn to the theatre, and began to work with Moshe Broderson, developing many of the small theatres of inter-war Poland. With the assistance of Yitschok Broyner, the two men created theatres including the 1922 Chad Gadya marionette theatre in ód, the 1925 Azazel theatre in Warsaw, the Sambatyon theatre in 1926 and the Ararat theatre in 1927. Kon continued to compose, specialising in music for the theatre. Kon left Poland before the war and moved to New York, where he was one of many Yiddish-speaking immigrant writers and artists who had fled Nazism. He continued to write and compose, and after the war committed his artistic production to commemorating the destruction of Polish Jewry.

Among other projects, he arranged songs of the Holocaust for voice and piano. He travelled extensively, to Europe and later to Israel. Kon died in New York in 1972. Henech Kon is best known today as the composer of the film score for The Dybbuk and his songs, such as Shpil zhe mir a lidele in Yidish.

He was, however, also a brilliant pianist and musicologist, and wrote arrangements for dozens of Yiddish songs and other scores, among them Freylekhe kaptsonim (Jolly Paupers, 1937). Born in Poland and educated in Berlin, he moved to Warsaw where he worked with the great writers of his time, and wrote music for their plays and kleynkunst performances. After fleeing Europe in 1940, Kon settled in New York, where his life was marked by an unsuccessful, constant struggle for work and recognition. By the time of his death in 1972, Kon had already become virtually forgotten, even in Yiddish musical circles. This lecture will present Kons life and work, and help to bring him the recognition he is due and his music back on stage. The item "Jewish YIDDISH SONGS Poems HOLOCAUST ART BOOK Composer HENECH KON Piano JUDAICA" is in sale since Sunday, May 23, 2021. This item is in the category "Collectibles\Religion & Spirituality\Judaism\Books". The seller is "judaica-bookstore" and is located in TEL AVIV. This item can be shipped worldwide.- Country/Region of Manufacture: Argentina

- Religion: Judaism